South America: The British Abroad (An Introduction)

The British had extensive banking and business interests in South America, as elsewhere in the world, by the second half of the 19th century. They were heavily involved in developing the rail network, which took them to every corner of the Continent. There they established institutions including schools, social and sporting clubs for the expatriate community, which usually focused on cricket and later expanded to include football as the sport grew in popularity. The present-day Argentinian league shows the legacy of British involvement in teams such as Banfield, Douglas Haig, Newell’s Old Boys, Quilmes, and Rosario Central, while across South America the influence remains evident in club names from Argentina’s Arsenal to Everton in Chile and Liverpool of Uruguay.

The founding father of football in Argentina was a Glaswegian, Alexander Watson Hutton. Soon after his arrival in Buenos Aires in 1882 he began importing footballs, which came to the country deflated and, legend has it, were passed through customs as ‘things for the crazy English’. A teacher, Watson Hutton founded the English High School before establishing the Argentine Association Football League (AAFL) in 1893 – Lomas Athletic Club became Argentina’s first champions. The English High School Athletic Club entered the newly-formed Second Division in 1899 and were promoted in their first season; re-named Alumni, they went on to win ten of the next twelve championships with a side built around the five Brown brothers. Without their own ground, and as the British community dwindled, Alumni disbanded in 1911, having made a lasting contribution to the development of Argentine football. The legacy of another emigrant, Isaac Newell, lives on. After arriving in the country at the age of 16, where he worked for the Central Argentine Railway, in 1884 Newell founded the Colegio Comercial Anglicano Argentino, and in 1903, his son Claudio was among the founders of Newell’s Old Boys, a football club for alumni of the college, in the city of Rosario.

Alexander Watson Hutton

Charles Miller

Just as in Argentina, the origins of Brazilian football lay in British expatriates and their cricket clubs, which were established in the major cities of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Bahia. The single most important figure in the game’s development in Brazil was Charles Miller, born in São Paulo to a Scottish father and Brazilian mother, and educated in Hampshire. A fine cricketer as well as a footballer, Miller played for the St Mary’s side in Southampton and returned to Brazil in 1894 determined to spread the sport in the country. Many of the leading teams reflected their class origins – the Fluminense club, founded in 1902 by members of the Rio Cricket and Athletic Association, restricted social membership to those of European descent until the mid-1960s. The growth of the game among the working-class owed much to another Scot, Thomas Donohoe, who set up a club at the textile factory in the suburb of Bangú where he was employed as a master-dyer. With Brazilian workers also joining, the Bangú club become the first team to win the Rio state championship in the professional era.

In the small republic of Uruguay, it was a Cambridge-educated Englishman, William Leslie Poole, who played a central role. He arrived in Montevideo in 1885 to take up a teaching post at the English High School, founded in 1874; an excellent athlete, Poole immediately encouraged students to take up the game. By 1891, workers at the Central Uruguay Railway Cricket Club (CURCC) founded a football club in the suburb of Peñarol, whose black and yellow striped kit was based on the colours of George Stephenson’s Rocket. A Scot, John Harley, is credited with transforming the playing style of Uruguayan football after his arrival from Argentina in 1909 to work for the Central Uruguay Railway, encouraging a refined passing game. He became player/manager of the Uruguay national side, winning 17 caps as an elegant centre-half, and then managed Peñarol, as the CURCC club were later known. Harley died in 1960, and is buried in Montevideo’s British Cemetery.

Everywhere the British settled in South America, they established sporting institutions alongside their businesses and schools. An English journalist, David N. Scott, founded Valparaíso Football Club in 1892 and helped to spread the game in Chile, which three years later became the second nation on the continent, after Argentina, to set up a national football association. One of the country’s pivotal early players was Juan Ramsay, Chilean-born but of British extraction, who was described as “English in all the acts of his glorious career.” In neighbouring Peru, one Alexander ‘Alejandro’ Garland is credited with introducing the game, though the country’s first official football match was not played until 1892. As elsewhere, the English cricket clubs capitalised on the new sport’s popularity – in Lima, Unión Cricket club even imported turf from Britain for its football pitch. One visitor to the country gave a first-hand account at the start of the twentieth century, just as the upper-class Anglo influence began to give way to working-class clubs across South America:

“Football seems to have an altogether extraordinary fascination for Latin-Americans, although it was a game completely unknown to them before it was introduced from England. Lima and Callao are very severely ‘bitten’ with the mania for furious football, and during the months of October-May it is played perpetually. Most enthusiastic are the players and, moreover, they play extremely well. The Callao team have a very competent captain in Mr Joseph Dodds… The Lima Cricket and Football Club is another well-patronized coterie of sport-loving men, and their games are watched by considerable crowds of interested spectators composed of both sexes.” [P.F. Martin (1911), Peru of the Twentieth Century]

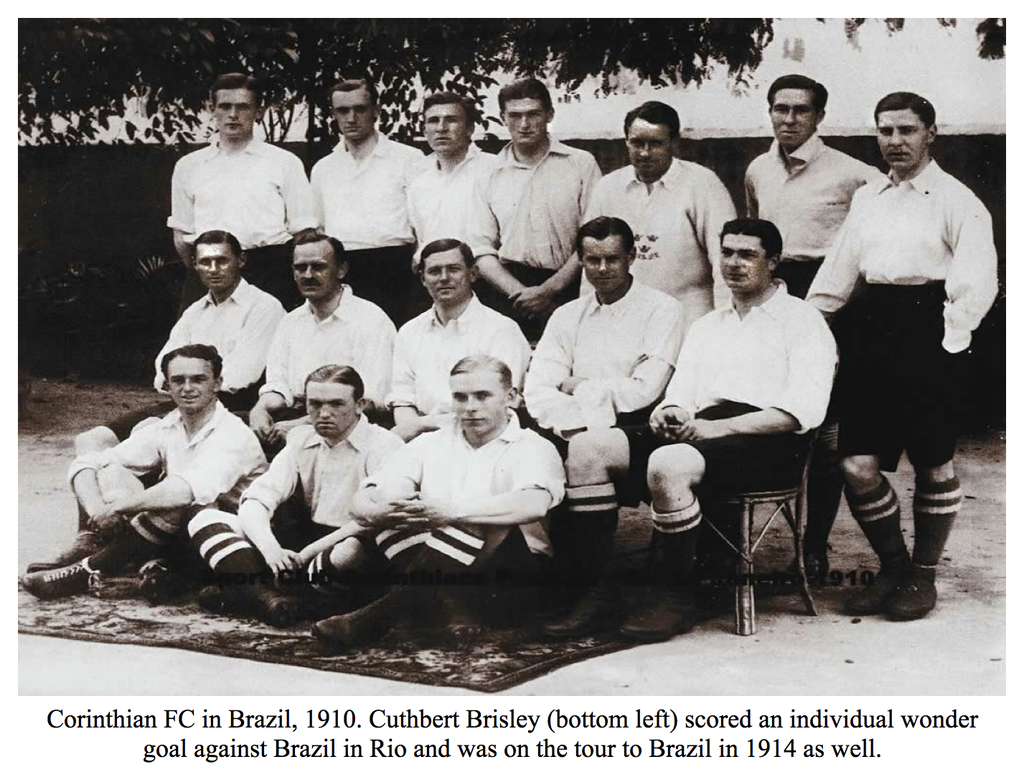

In addition to the efforts of the ‘founding fathers’ in these countries, the initial impetus of the sport was further boosted by the successful tours of English sides to the Continent, led by Southern League side Southampton in 1904 and Nottingham Forest a year later, and followed by Everton and Tottenham in 1909. Forest’s tour of 1908 made such an impression on the president of Argentine club Independiente, that the team’s colours were changed to match the red and white of their visitors. The visit of the famous amateur side Corinthian F.C. in 1910 inspired a group of railway workers in São Paulo to form a football club – the Brazilian Corinthians became one of the most successful teams in the country. Swindon Town’s secretary-manager Sam Allen, who toured in 1912, reported: “I have never seen such enthusiasm for the game as shown by the two Republics [Argentina and Uruguay] and everywhere one sees the hold it has taken on the people.”

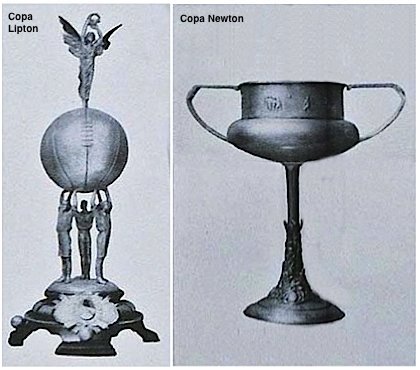

Britain had seen the birth of international football, with England first playing Scotland in 1872, and ex-pats soon introduced the idea to South America; in 1889, one of the earliest international fixtures outside the UK took place at the Montevideo Cricket Club, between Buenos Aires FC and Montevideo FC. “Set up by local British residents and staged on Queen Victoria’s birthday”, as Tim Vickery recounts, the annual challenge “took place in an atmosphere of aristocratic chivalry. It was common for penalties to be struck wide on purpose in an acknowledgement that an opponent could not possibly have intentionally committed a foul in the area.” In the early twentieth century, the rivalry between Argentina and Uruguay intensified with the introduction of the Copa Lipton, a trophy donated by the Glasgow-born magnate Sir Thomas Lipton with the stipulation that the teams be made up of only native-born players. The cup itself was commissioned by Lipton from an English silversmiths, most likely Elkington & Co of Regent Street. The trophy was contested from 1905 until 1992, although only intermittently after the 1930s. The concept was copied by Nicanor Newton, president of the Argentine Football Association, whose Copa Newton began in 1906, with the opening goal scored for Argentina by Arnold Watson Hutton, Alexander’s son, and was last contested in 1976. Argentina and Uruguay remains the world’s most frequently played international fixture.

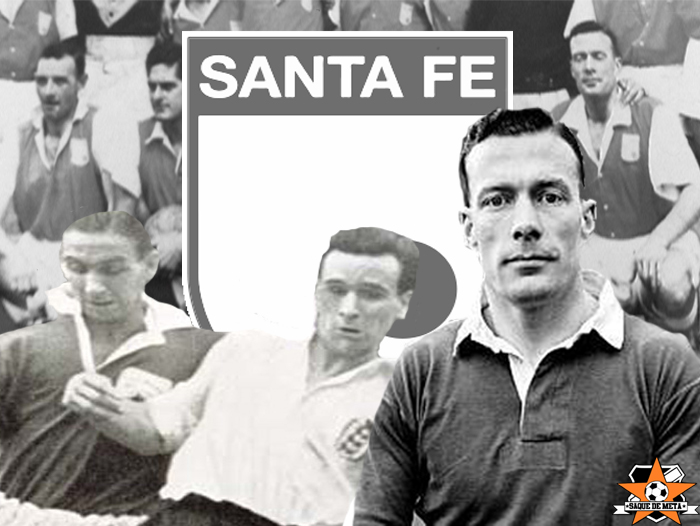

While the movement of players (and managers) has been overwhelmingly from South America to Europe since the early twentieth century, there are a few instances of Brits moving in the opposite direction. William Reaside managed Nacional of Uruguay in 1939, and Newell’s Old Boys in 1947, while Randolph Galloway had a spell in charge at Peñarol in 1948; Neil McBain lasted longer at Estudiantes of La Plata, where he was manager between 1949 and 1951. The brief flowering of a ‘rebel’ Colombian professional league operating outside FIFA regulations between 1948-53 saw an unprecedented number of imports brought in from across the world, as clubs were under no obligation to pay transfer fees. Since this coincided with a players’ strike in Argentina, several stars such as Alfredo Di Stefano and Adolfo Pedernera, an idol at River Plate, came to Colombia’s ‘El Dorado’. The league even imported a number of British referees, and saw a short-lived influx of players from the UK. Attracted by salaries far in excess of the Football League’s maximum wage at the time, Neil Franklin and George Mountford of Stoke, and Manchester United’s Charlie Mitten, all joined Santa Fe, while Billy Higgins of Everton and Scottish international Bobby Flavell left for their big-spending Bogotá rivals, the appropriately named Millonarios. While FIFA soon intervened to end the Colombian’s league’s illegal ‘poaching’, all of these players faced sanctions on their return to Britain. England international Franklin was the most prominent of the rebels, and paid a high price, suspended by the FA and Stoke, who soon sold him to Hull City. Today, the only British player currently active in South America is George Saunders, an English midfielder playing with Envigado in Colombia.

Various books and websites helped in my research for this article; one I can recommend is ¡Golazo!: A History of Latin American Football by Andreas Campomar. He is a Uruguayan author and the great-grand-nephew of Dr Enrique Buero, the man who persuaded Jules Rimet to stage the first World Cup in Montevideo and later became Vice-President of FIFA.