Derek Goodier: An Interview (Part One)

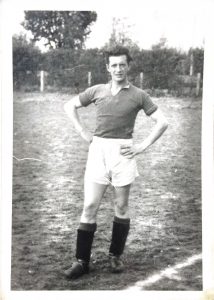

I have had many football conversations over the years with my father-in-law, Derek Goodier, who was playing and watching the game as early as the Second World War. When I started the blog, I decided to interview Derek, to capture his wealth of knowledge and experience. He kindly shared his memories of Stanley Matthews, Stoke City, his time playing in Germany and much more relating to football in the previous century.

Can you tell me about your earliest experiences of football – playing and watching?

My earliest recollection of watching football was 1943 when I was five years old at Stoke, the Stan Matthews era during the war. I had a lull and then I started watching Stoke regularly with my dad which would be about 1947 – aged eight, I was watching them then. I was playing football too, a junior, I was nine, eleven; no such thing as coaching or anything like that. No such thing as goalposts or nets. I’d got an old ball stuffed with grass and you just went along like that. No such thing as football boots, you were barred from playing football if you wore clogs so you had to play in your bare feet or stocking feet, and that was my first introduction to football. Nothing like grass – mostly cinders, gravel, red ash or tarmac if you were lucky. No niceties at all. Nothing like eleven-a-side, it was more like thirty- to fifty-a-side. No referee, no nothing. Whoever got the ball was very lucky.

And how did you begin playing organised football, was that through school?

At school – when I went to the senior school because there was no organised sport at junior school. I was eleven / twelve when I went there. It stood you in good stead playing with plenty of people because it seemed as though you had more space. Still no strips or anything like that until later on when you came into the last two years at school. I had a pair of football boots by then. There was no such thing as socks but I’d got a pair of boots and a heavy old ‘casey’ [football] which was a number five – as young lads you could probably move it about ten / twelve feet. You wouldn’t move it any farther. It was too heavy and if it was wet you didn’t move it ten or twelve feet, it was more like six. It was a big case ball because the case balls then came in different sizes. That was the number five size, that was the big one. All leather with a rubber inner tube inside and a lace. When you tried to kick it and you didn’t quite catch it right – there was no such thing as trying to volley it as a young lad because it would break your ankles. You couldn’t head it, you couldn’t catch it on your chest because the ball was just too heavy, too big. So you progressed from there and when you were about fifteen you started getting the hang of it. You went forward from there and joined a team, and if you were good enough you were picked and I was picked at sixteen to play for Kidsgrove United.

It was an introduction to something very hard because football then was really, really, hard. There were no questions asked, you just had to get in on it and you spent more time flying through the air or being kicked. But you learn – you had to learn the hard way. You had to be clever, you didn’t stand about, you got the ball to your feet and did your best and tried to get round somebody and beat ‘em and that was how it was played, football then. If you hadn’t got the skill, you’d get all the knocks so you learned skills pretty quick.

What position did you play and who decided that?

Who were your favourite players? Was there a player who inspired you, who you modelled your game on, or that you would have looked up to at that age?

Well, the players that you looked up to at that age when you were playing out on the wing were Stan Matthews on the right wing and Tom Finney on the left wing. And if you could get anywhere near one-one-hundredth of what they were like, you were doing alright because they were phenomenal players. But you always thought in your own mind ‘I could do that’ but it is very hard to throw a dummy, especially to throw a dummy to feign to go inside and go outside because you’re on the wrong leg to push off. You can’t do it in the same way as the professional players but you learn about it, you learn how to do it.

And that was quite a high level that you were playing at with Kidsgrove wasn’t it?

Some moved on [to professional football] and some couldn’t afford to move on. It was a time [mid-1950s] when you couldn’t move on because of home commitments – then you were expected to pay in to the home finances, that was part and parcel of your life. You couldn’t afford to become a professional footballer. You were very lucky if you could, so there were very few who went that way. When I first started playing football at that level, the reserves from all of the big central teams such as Wolverhampton, West Brom, Stoke – if they were coming back from injury, they were playing in the same league as I was playing in. So it was no easy task, no easy task at all.

You were playing against professionals – were there any in particular that you remember being tough opponents?

Johnny McCue from Stoke warned me off; he said ‘don’t try to be clever and you’ll be alright’. So I took him at his warning and just played a normal game and come off unscathed, otherwise I think I’d have been about ten feet up in the air and learning how to fly because he was unforgiving, that bloke was. But I played against a lot of professional footballers and you learn a lot from them if you watch them because they are very clever. They are not as clever now, they are more cynical.

What were your experiences after Kidsgrove – where else did you play and at what level?

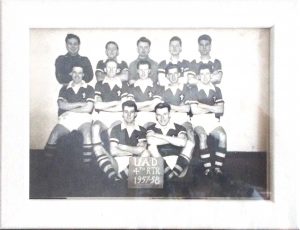

I played at Kidsgrove until I joined the army. I went into the army, the R.E.M.E. [Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers] and was attached to the Royal Tank Regiment and the players they had there were something else. The army teams could only play four players in any one team, four professionals and the rest had to be amateur. So I was with Jack Maltby, who was the centre-forward for Sunderland and Billy Day, who played on the wing for Middlesbrough alongside Brian Clough. He was Brian Clough’s main supplier at one point. Halliday who was a goalkeeper and a bloke called Brocklehurst or Brocklebank – I forget now, it’s a long time ago – he was a centre-half, he played in the Scottish League. And to play football with them was an education because they made football so easy – especially Billy Day – Billy Day was phenomenal, the pace and the control was unbelievable. And Jack Maltby, he was just a centre-forward of the old type – the ball, the goalkeeper and everything went in the net. It didn’t matter. If the ball was in the area and the goalkeeper was there, as long as he had his feet on the ground he was fair game for going back of the net – bang. It was a hard game.

When I was there [stationed in Fallingbostel, Germany] we used to have German lads come and watch football games because you had a lot of professionals out of the English League and the Scottish League. I was approached by the manager of Dorfmark TSV who were a semi-professional side and they wanted us to play for them, so three of us went – me, George Baker and Rob Burns. Where I played was in the third tier of the Bundesliga. The three of us in that team were like the enforcers, for want of a better word, we dictated how they played. They used to pay us [five marks], which supplemented our army pay, which was great. Everything was great, changing facilities, pitch, everything – phenomenal. And our football was a lot harder than theirs. They were what we called ‘half and half men’. If there was half a chance of getting it, they’d pull out and you’d get it. We were a lot harder than they were going in for the ball, it was a stand-off game for them, more like it is now, and I think they admired our tenacity – you know, to get in at ‘em. I had some good times with them, playing football for Dorfmark TSV – I was with them from the end of 1957 to March 1959. I had some good times, met some good players and had some good friends, German blokes.

To go back to watching football, you first went to Stoke, the Victoria Ground around 1943 during the war-time leagues and that continued when league football resumed. Could you just say a bit about the experience of going to a match then, how it was, where you watched the game from, the crowds etc.

Well, the thing is when you went to Stoke and you were only small, you weren’t allowed on the ends behind the goals, they were for adults only. You could go in the paddock – if you couldn’t afford to go in the stand, you went in the paddock. And what happened when you went in the paddock with your parents, I was with my father, you were passed down over the crowd and put on the running track round the outside, and then you’d got the grass and then the line. So you were put down on there to watch the game. That’s how you watched the game, all kids together sitting on the running track.

So you had a close-up view of Stanley Matthews and other players at the time. I imagine it was amazing to watch him at close quarters?

Oh yes, it was. He was a phenomenal player, he was fast over ten yards, phenomenally fast. Deceptively fast and the way he could drop his shoulder to feign to go right, drop it to left and go right was unbelievable. I’ve never seen a bloke like him, it was like the ball was glued to his foot, unbelievable player. He never got booked in his life, he was just a phenomenal footballer. Never see the like of him again, I’m just happy that I managed to see him. He was a phenomenal player. Oh, he was adored at Stoke, everybody loved him at Stoke – that was what everybody went to watch, Stan Matthews. When he got the ball, the roar was unbelievable.

My next question is about the noise and the atmosphere at the grounds. How did you find that – were the crowds particularly biased to the home team? Would they boo away players or was it a more fair-minded atmosphere?

No, it didn’t matter if he was a home player or an away player. There came some fantastic players to Stoke that I saw. It didn’t matter who they were. If they were playing and they were brilliant and they did something, they were cheered. They cheered the football. They liked the home team and wanted them to win obviously, but they cheered the football. It was more about the football than having an allegiance to one club. They enjoyed the football.

And were there any players, either Stoke (other than Stanley Matthews) or opposition that stay in your mind as being particularly enjoyable to watch?

Yes, blokes like Len Shackleton and Ivor Allchurch, Tom Finney, people like that, ball players. Lovely, lovely players. Beautiful players, they could do anything with the ball. And we have to remember they were playing with a ball that was heavy. A ball then could weigh anything up to 7lb in weight when it was wet, I mean these balloons they play with now – unbelievable. These blokes were phenomenal with the skill they had with a heavy ball, heavy pitches. Pitches not to the standard as they are now. I mean, they were just like playing on a ploughed field for want of a better description, because they were always muddy – there were no training facilities, the team trained on there every day of the week, played on there on a Saturday. Probably the reserves played on there in the mid-week, so it was getting used all the time. There was never a blade of grass between the D and the goal, it was always mud and sand. It was really hard work but there were some brilliant, brilliant players.

You see in the 1950s and early 1960s you didn’t go up there [the Victoria Ground] just to say ‘Come on Stoke, Super Stoke’, which they were anything but. You used to go up there and say, today Len Duquemin’s here with Tottenham, or Len Shackleton’s here – you went to watch that player, you knew those players would respond and play – Raich Carter, you know all the brilliant players. That’s what you went to watch. That was the heart of going to football then, just to watch the others. And if you could beat that team with the star in them, then fantastic. But Stoke had their own stars. They had Neil Franklin, who’s the best centre half I’ve ever seen in my life. He used to go through a match and not a hair on his head was ruffled. He never had mud on his shorts or anything; by God did he win some tackles, but he didn’t have to go down for them. His positioning was phenomenal. Different era. Different game.

During my time of watching football from the 40s to the 70s, the people you most liked to see were the goalscorers. In the 40s and 50s you had Milburn, Mortensen, Steele, Lawton, Rowley, Lofthouse, followed by Smith, Taylor, Clough and [later] Astle, Ritchie, Osgood – what a bunch of centre-forwards! And of course you had players like Greaves and Law – what price these players, and where are their equivalents now?

And were there any teams that stood out, which were most impressive?

Yes, Tottenham at that time were impressive, very impressive. They were playing a style of football which was called ‘push and run’. As soon as you moved the ball, you ran to another space. It didn’t take out the dribbling aspect or anything like that, but you always made for a space which you never did before, because once you’d made a pass you ambled up or run up or whatever, but you never run for space. That showed you that you could run for space and make things happen, because there was nobody there to take the ball off you until people caught on to it and started man-marking. Before that it was like block [zonal]-marking, everybody marked up, and whoever came into your territory you tackled, but after that they started man-marking.

As the years went on, obviously you were following Stoke. Did you ever go to other grounds either to watch Stoke or to watch another team?

I went to every ground in Division One. I went to most of them in Division Two when Stoke were relegated. I used to enjoy visiting the other grounds, some of them were great to go to. And some of the teams were really good to watch and you got an insight into football – everybody seemed to be more for football than they were for their own team. They followed the football. There was no tribalism, cat-calling and shouting at one another or anything like that; no, it was just going to watch football and the crowds were phenomenal. Massive crowds, bigger crowds than you have now because it was all standing apart from the upper stands where the directors were. I mean when you talk about being on Stoke with 60,000 – I mean the old Stoke, Victoria Ground. I’ve been on Hampden with 100,000. I’ve been on Rangers ground and Celtic ground on New Year’s Day at the Old Firm matches. The experience is phenomenal.