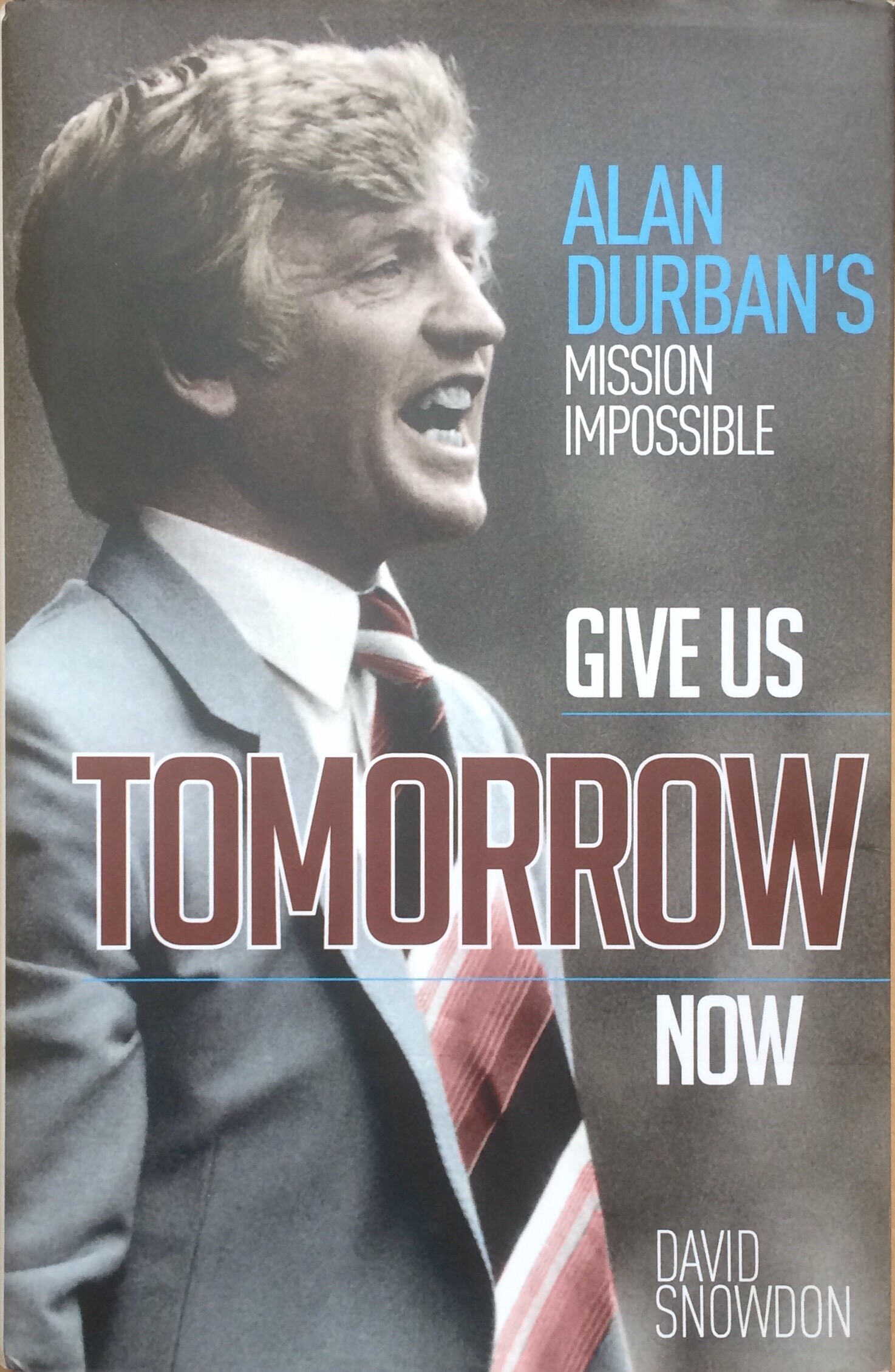

Give Us Tomorrow Now: Book Review & Interview with author David Snowdon

Give Us Tomorrow Now: Alan Durban’s Mission Impossible (Pitch Publishing, 2018) by David Snowdon reconstructs Alan Durban’s managerial reign at Sunderland with a wealth of detail, from his appointment in the summer of 1981 to his untimely sacking in March 1984.

The background to the book is a very different era of English football, with even the biggest clubs forced to cut costs amidst falling attendances and before the major injections of sponsorship and television money. Austerity had arrived and the spate of million-pound transfers was coming to an end; hooliganism and the neglected condition of many grounds contributed to the 1980s being a tough time for English football off the pitch. Aston Villa were the reigning league champions, while Liverpool compensated for losing their title by lifting the European Cup in May 1981 – the fifth triumph in a row for English clubs . England’s place in the 1982 World Cup was still uncertain after a difficult qualifying campaign. The 1981-82 season introduced three points for a win to the Football League, which also saw QPR become the first team to play on an artificial surface.

In this context, Durban left Stoke to take over at a club only recently returned to the First Division, and in his first season Sunderland’s average attendance at Roker Park fell by almost 7,000 from 1980-81. Crowds continued to fall steadily as the novelty of their return to the top tier wore off, down to just over 16,000 by the end of 1983-84. This decline only reflected a general trend in English football. However, Sunderland’s potential (a key theme of the book) remained – even as a struggling Second Division club in 1985-86, they still recorded a higher average attendance than many top-flight clubs. By then unfortunately Durban was long gone.

He began by spending a club record transfer fee of £355,000 on a young Ally McCoist, while developing home-grown talent such as Nick Pickering (capped by England in 1983) and Barry Venison (later of Liverpool and Newcastle and a future England international). Denied further funds, Give Us Tomorrow Now portrays Durban’s reign as a balancing act; scouring the transfer market for bargains (Ian Atkins) and free transfers (Leighton James) while trying to temper unrealistic expectations in the boardroom and on the terraces. Hampered by a shortage of staff (coaching, medical and playing), with cost-cutting imposed on him at every turn, the manager even turned out for the reserves.

The book underscores his determination to slowly rebuild despite these restrictions, and the enforced sale of McCoist to Rangers in the summer of 1983 (at a loss). Durban continued to add proven quality to his squad (Paul Bracewell, Lee Chapman, Mark Proctor), improve team spirit and make the side hard to beat. His progress was evidenced by steady improvement in league position in each season. Sunderland were in 12th place at the turn of the year in Durban’s final season, level on points with Spurs and above Arsenal and Everton, eventually finishing 1983-84 in a respectable 13th place. The decision to sack Durban looks especially short-sighted given the club’s subsequent relegations in 1984-85 and 1986-87. Not until the arrival of Denis Smith to lead the club out of the Third Division in 1987-88 did Sunderland’s fortunes revive. That Durban was not given time for his long-term vision to come to fruition is a source of regret for the author and, I suspect, many Sunderland fans.

David Snowdon kindly agreed to answer a few questions about his excellent book, and the state of English football at the time.

Could you just introduce yourself and give a little background on your early football memories and history with the game?

I’m David Snowdon. On leaving school, I worked for a building society for 15 years, before leaving to pursue full-time education, eventually culminating in achieving a PhD in English Literature. Subsequently, my first published book (Writing the Prizefight) was awarded the Aberdare Literary Prize 2014 by the British Society of Sports History.

Despite growing up in a household that did not follow football, I started to support and follow the fortunes of Sunderland AFC around the 1974-75 season. My first match attended at Roker Park was in December 1975 during the team’s successful 2nd-Div. championship winning season, but for the next few years, apart from the occasional treat of being taken to a match by an uncle or friend of family, my support was restricted to being glued to local radio, and watching football programmes on TV.

I was able to buy a season ticket to attend matches on a regular basis in the summer of 1981; the summer of Alan Durban’s arrival as manager. I retained this ticket through thick and thin until 1993 when other commitments prompted me to ‘retire’ from attendance.

Throughout this near 20-year period, my obsession with football was a broad one, devouring information and news on an extensive range of teams, players, and happenings across all four divisions, plus Scotland. However, I consider the period 1975-1990 to be my specialty for in-depth detailed knowledge.

Alan Durban’s reign might be considered a bit of a niche subject – why did you choose to write about this topic and particular era in Sunderland’s history?

As mentioned, this period coincided with my first season-ticket regular attendance of games. The memories are seared into my brain as fresh as if they were weeks old. Crucially, I felt the story of this episode in Sunderland AFC’s history was a neglected one. All of my favourite football books are on topics and people that that have not been ‘done to death’ or had saturation coverage showered on them. I for one do NOT want to read anything about, for example, a couple of certain South American ‘superstars’ (even if one did play throughout the 1980s)!

Give me the road-less-travelled, under-analysed topic any day. Books on Dennis Tueart, Ron Saunders, Malcolm Allison, Steve Hunt, Bob Latchford – these are the ones that are truly insightful and fascinating to me. They are also universally accessible in the sense that the reader merely had to be interested in football in that period (regardless of which, if any, particular team supported) to enjoy or find the book enthralling. I endeavoured to, and believe achieved, infusing Give Us Tomorrow Now with those fundamental qualities.

The book places Durban’s time as manager in the context of English football in the early 80s, including events on and off the pitch, transfers at other clubs – what are your overall impressions of the state of the Football League at this time?

As an obsessive follower, I loved it. It had its shortcomings and faults no doubt, but apart from the obvious lingering hooliganism element that pervaded for years, most were obscured and rendered relatively inconsequential through the eyes of youthful enthusiasm and zest for the game. There seemed to be top-quality matches every week, and the players were familiar household names. With clubs operating with first-team squads of around 15-18 players, football followers back then could probably still reel off a host of teams’ regular line-ups and back-ups.

While there may be an element of rose-tinted nostalgia in my sentiments, less was definitely more. TV coverage was at a premium [& live games few and far between] compared to the saturation 7-day a week programme of matches churned out now. We would avidly tune in to either Football Focus or On the Ball on Saturday lunch-time [they usually overlapped one another], highlights of two [three if lucky] matches on Match of The Day and the regional ITV programme [variations of The Big Match]. Many will probably identify with listening to Radio 2 Sports Desk bulletin at 9.55pm or, when off school, the brief afternoon hourly version at 1.45pm, 2.45pm etc. Any scraps of football transfer news would be devoured greedily.

As I say, less was more, what coverage there was was savoured and appreciated. Times seemed good; they were good!

You talk about a mood of cautious optimism at Durban’s arrival in the summer of 1981 – what do you think were realistic expectations for Sunderland at that point?

Permit me to quote a passage directly from Give Us Tomorrow Now to provide the answer to this one:

‘For the majority of Sunderland followers, [it was] finishing well clear of the bottom three and not having to endure the emotional turmoil of a nail-biting final game with their First-Division status teetering on the brink of the abyss. Yes, mid-table paradise; that would do very nicely Mr Durban, thanks’.

After Middlesbrough’s relegation, and with Newcastle still in the Second Division, Sunderland were the north-east’s only top-flight side at the start of 1982/83. Do you think this was a missed opportunity for the club to establish itself as the major force in the region [before Kevin Keegan’s arrival]?

To an extent. However, clubs pushing for promotion from lower league have historically generated a greater degree of enthusiasm, interest and attendance levels than clubs struggling to maintain top-flight status.

Nevertheless, great things could have been achieved if Sunderland’s board of directors had backed their manager’s transfer judgement and shared his vision to ‘upmarket’ the club. Newcastle directors reaped the rewards for ‘speculating to accumulate’ as the Keegan swoop paid rich dividends on and off the pitch.

Repeatedly you discuss Durban missing out on transfer targets for various reasons – which of those players do you think would have had the biggest impact?

I think the failure to secure Jimmy Nicholl when the international defender was prepared to sign permanently was a major error; the board having the chance to finalise a £225,000 permanent deal in February 1982. Months later, Nicholl did return temporarily but by now was tied to the NASL and Toronto Blizzard.

That same season, the almost-realised return of former 1973 local hero Dave Watson [age 35] would probably have generated greater solidity, and an emotionally-charged benefit over an 18-month contract.

The board simply did not provide Durban the realistic funding to really push for Ipswich’s John Wark, and I suspect the greater attraction of going to Liverpool would have held sway in that case. I feel that Craig Johnston was the transformative player who realistically might have come to Roker Park if he suspected he was not going to get his chance at Anfield, but the necessary hefty funding was never available for Durban to properly test the theory.

Ironically, one of the most enduringly beneficial pieces of ‘transfer’ business would have been for the board to finance Durban’s midfield revamping [Bracewell and Proctor] in the summer of 1983, and not render it necessary for him to raise the lion’s share of the funds through the sale of Ally McCoist to Rangers – the sacrifice was an unpalatable one.

Personally, I feel that one man that Durban did not miss out on through lack of backing was extremely early on in his tenure. The manager subsequently realised he had erred in his assessment of Everton’s Bob Latchford as a risky “gamble”. The former England striker (and 30-goal season man) had suffered a final season at Goodison blighted by a slow-to-mend hamstring injury. However, he had used a summer stint in Australia to regain tip-top condition. In fact, in his excellent [auto]biography, Latchford records that he arrived at Swansea a refreshed man feeling as physically fit as he ever had been and, between 30 and 34, felt as strong as when he’d been between 20 and 24. As well as the goals and ‘assists’ Latchford would have supplied in his own right, crucially, his physical presence and wealth of experience would have undoubtedly expedited Ally McCoist’s acclimatisation to the English top flight. I believe that as well as the power of good Latchford would have done the Sunderland team, McCoist’s speedier development as he learned from the big man’s penalty-area nous would have seen the Scot settle down and start scoring more frequently, leading to him being an established part of a successful Sunderland team for many years.

However, regardless of what I think, much credence should be attached to the insightful ‘inside’ line supplied by Alan Durban and Nick Pickering when they spoke at a book-related function held in Sunderland two years ago. England internationals Mick Mills and Mark Chamberlain were the two that were specified as the ones that would have really made an impact. Despite Mills being 32, his all-round experience, quality, and influence would have been immense. In addition, Mills operating in a left-sided defensive role would have solved an eternal dilemma for Durban, allowing him to release Pickering to perform his foraging attacking midfield role full-time. The Mills move almost happened [see book]! Although the link with Chamberlain was officially quashed at the time (late 1983), the wide-man’s friendship with his former Stoke team-mate Paul Bracewell lends substance to theory that Sunderland did indeed have a head start in securing his services to maraud down their problem right flank area. This new 2020 statement from the two former Sunderland men makes it evident that the deal had been a distinct possibility, and one that Pickering singled out as potentially pivotal.

Thanks to David for providing many of the images which accompany this article – he can also be found on Twitter. He speaks at length about Give Us Tomorrow Now in a two-part episode of the English football history podcast When Shorts Were Short.

This is a superb synopsis by David Snowdon who has a encyclopedic knowledge of SAFC during the Alan Durban period and, having read the book myself, will say it is an absolute “must read” text for ANY SAFC fan.

Thank you for taking the time to read and comment, Howard. I really enjoyed the book (though I’m not a Sunderland fan) and much appreciated the chance to ask David about it, and English football generally in that era. I plan to post the second part of his interview next week.