David Snowdon: Give Us Tomorrow Now Interview, Part Two

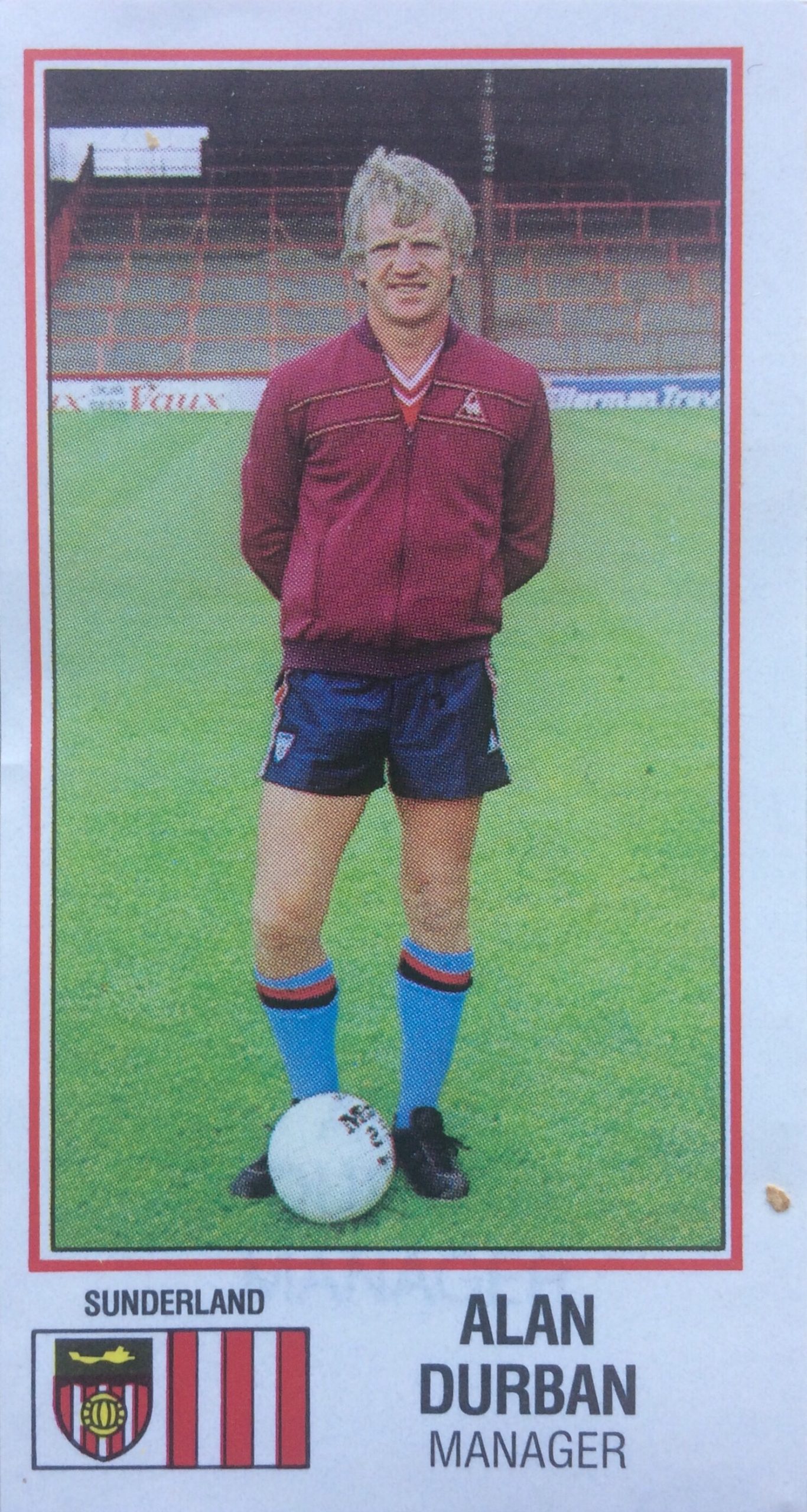

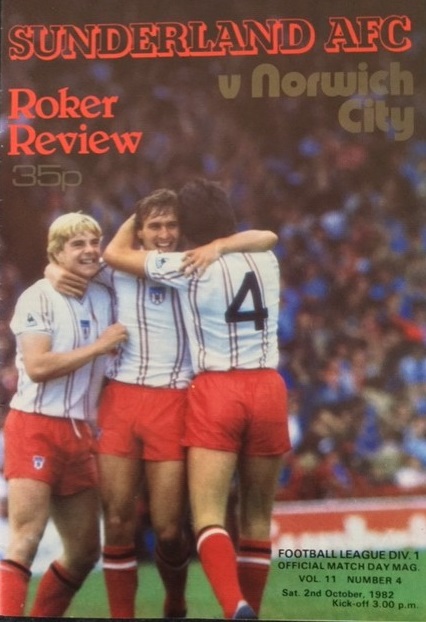

David Snowdon continues to discuss his book Give Us Tomorrow Now, charting Alan Durban’s time in charge of Sunderland, and English football of the day – Part One is here.

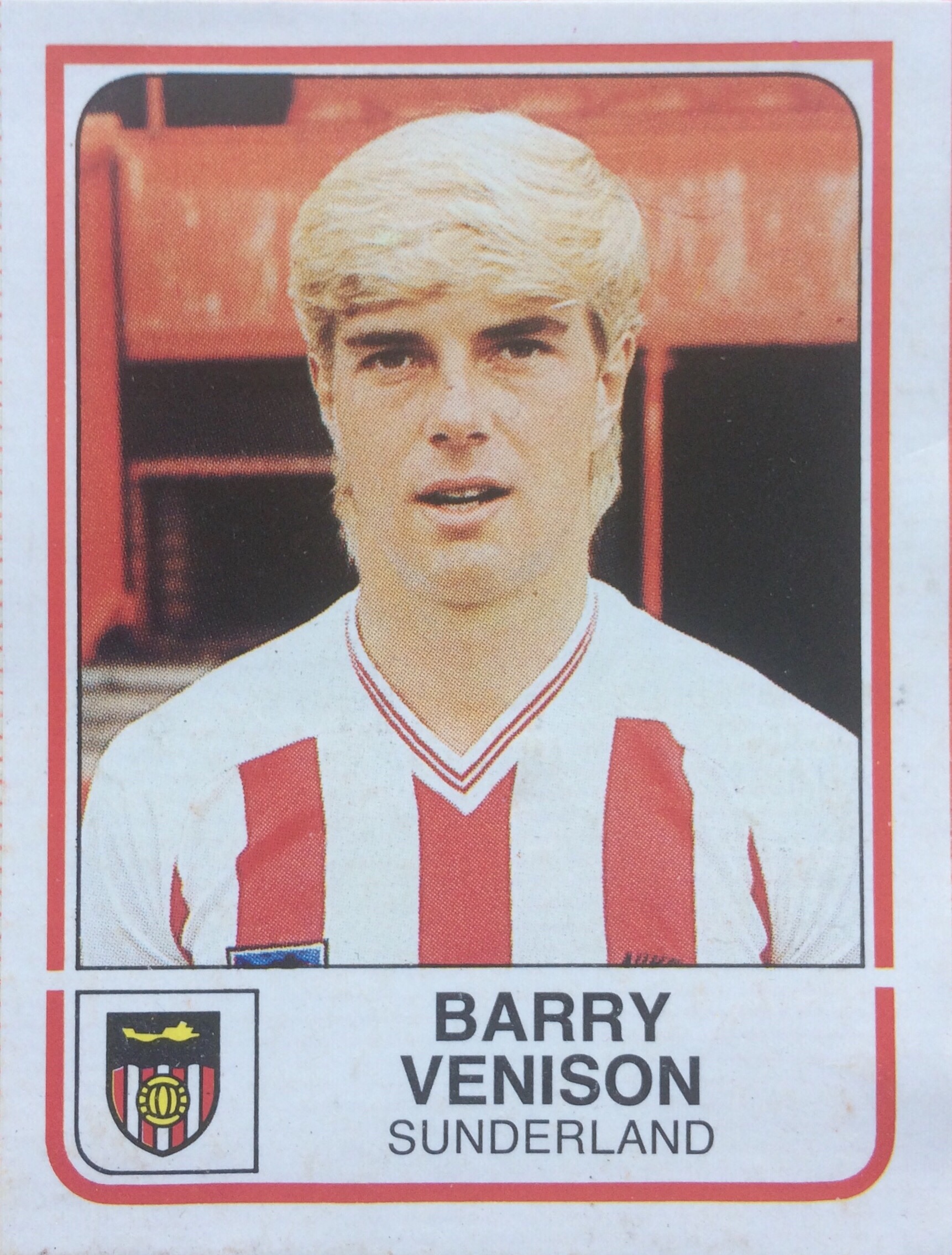

The area was renowned for producing players – you mention Kevin Dillon, Mick Harford and Mike Hazard, and Nigel Gleghorn was another, a Sunderland fan playing non-league football in the region. While Atkinson, Pickering, Venison and West were all given first-team opportunities, was the club making the most of local talent and how important was that to Durban?

Securing the cream of North East and Scottish talent was of paramount importance to Durban. He reprimanded the club for past failings and set about overhauling the scouting system and credo in an attempt to remedy the situation. As early as 12 months later, two useful midfield finds were netted in the form of John Cornforth and Gordon Armstrong.

Durban continued in his aim to assemble a squad brimming with locally-sourced young players despite seeing his coaching and scouting resources diminishing (along with everything else) by a parsimonious board lacking in football knowledge and foresight.

You portray a manager having to organise friendly fixtures, change the reserve team’s league and undertake scouting missions as well as his first team responsibilities – do you think this was a distraction, or just seen as part and parcel of a manager’s duties at the time?

It was an accepted part of a football manager’s role, and Durban was a very ‘hands on’ manager anyway. He liked and preferred to have the task rather than leaving it to directors and administrative ‘suits’ who he had been decidedly irked by on his arrival in 1981 after the club leased three of its first-team regulars to play in NASL, thus denying Durban their services for season start. In addition, Durban criticised the pre-season friendly schedule he was confronted with which would have led to players reaching full match fitness prematurely with first league match still weeks away. As the book explains, the admin side would also botch the contract renewal process that led to the club losing out on a substantial sum when one of their saleable assets claimed a free transfer as a result of the admin howler.

How do you think supporters viewed Durban’s sacking then and now – has his reputation among fans been reappraised in light of the club’s fortunes afterwards?

Opinion was divided, depending on whether one had the vision to see ‘the big picture’ and that significant inroads had been achieved and solid foundations established as Durban had built a harmonious squad, pulling in same direction, containing the desired blend of youth and experience. However, the vocal minority, crucially including certain board members, were blind to that progress. Predictably, as one journalist phrased it (as early as 1987, after Sunderland had slid into the 3rd Division for the first time in their long history): ‘Subsequent events have improved some people’s eyesight’.

Why do you think he never returned to top-level management, despite being relatively young; did the infamous ‘clown’ quote at Stoke influence his public perception as a defensive manager and affect his subsequent career?

I don’t think the misquoted ‘clowns’ myth was an issue. Durban himself admitted that taking on the forlorn task at the club where he started his playing career, Cardiff City, was a mistake, perhaps dictated by emotion rather than sound judgement. It is baffling to think that Cardiff, under Ashurst’s charge, had been at wrong end of Division 2 table when Sunderland took their former left-back on as Durban’s successor. My book mentions that Durban had been wanted in his first two post-season summers on Wearside by two fallen giants, Leeds Utd and Manchester City, to revive their fortunes and restore them to the top flight. If Durban had sat tight until the predictable spate of managerial casualties had fallen during the subsequent 1984-85 season, then I am sure he would, once again, have been approached by a relatively big club, or one with rosier prospects than impoverished Cardiff.

After that, it also needs to be considered that Durban, as much as he loved football, was [is] a “sports nut” with a broad palette of sporting interests and in-depth know-how. He was quite content to apply himself to accepting high-level roles in other areas, including one of his passions, tennis.

Durban later undertook scouting duties and, as mentioned in the book, recommended to Sunderland boss Peter Reid that it would be worthwhile to push ahead with their interest in a certain striker called Kevin Phillips.

Would you consider a sequel covering the rest of the decade [Len Ashurst, the Milk Cup final and relegation from the First Division, and of course Lawrie McMenemy’s reign] or are the memories too painful?

I am capable of writing such a work, but my heart would not be in it. To pore over Ashurst’s subsequent dismantling of Durban’s flourishing squad and narrate its dramatic degeneration in quality and character would be depressing. Many fans’ eyes were turned by the transient glitter of a run to Milk Cup final, but many other supporters like myself were always far more concerned with the worrying league form. Of course, the cup run did generate income which was primarily used to secure McMenemy and Lew Chatterley, with the remainder being, predominantly, spent on transfer fees and attractive contracts for ageing players who struggled to adapt to Division 2 football life.

In addition, certain reminiscences by former players that were omitted from Give Us Tomorrow Now because they were superfluous would have to be told if narrating events of the 84-85 season. They are highly critical of Durban’s successor, showing him in a poor light, and I wish to avoid producing what might be perceived as a ‘hatchet job’.

Any future book by myself on Sunderland would not be a sequel. I am currently mulling over and refining a final writing project to settle on but, given the amount of hard work and commitment involved, it must be one that does not pose risk of becoming a tedious chore, but one that is enduringly absorbing and fascinating – as Give Us Tomorrow Now certainly was.

The book does a wonderful job of evoking Sunderland’s struggles and English football in the 1980s – is your interest in the club and the game as strong today?

The short answer to the question would be “no”! I stopped attending matches in 1993, but continued to follow and support Sunderland. Often, I would find myself watching Match of the Day not having heard any football results that day, and the old ingrained feelings would swell up as I internally urged the team to score or hold on for a good result. Even as recently as 2015, I could have the blood stirred by the inspirational attitude of Dick Advocaat amid the securing of top-flight safety. However, I have not watched any football since around 2020, at any level. It leaves me cold; it is a different animal to the game I loved and avidly followed years ago. I’d better stop at that otherwise my answer would slip into being a verbose diatribe against the media-hyped, emotionally-hollow, inferior-quality ‘product’ that it has degenerated into. Soulless saturation! Nowadays, I stick to viewing editions of The Big Match Revisited.

Thanks to David for providing many of the images which accompany this article – he can also be found on Twitter. He speaks at length about Give Us Tomorrow Now in a two-part episode of the English football history podcast When Shorts Were Short.

The knowledge that David Snowdon has of this period in Safc’s history is both deep and encyclopaedic.

He kicked every ball in this era – and, as a season ticket holder since 1992 (on the verge of packing it all in) – I agree with his sad reflections on where the beloved game is right now – I also find it hard to muster any enthusiasm for the professional game especially when you look at who is in charge at say Chelsea or NUFC –

Well done David I look forward to reading your next book which I am sure will follow your passion again

Thanks again Howard – it really is an excellent book and very interesting to read David’s thoughts on the game then and now – also looking forward to his next book!