Conclusion: Foreign Players in the Football League

This series on the history of foreign players in the Football League reaches its conclusion. Over 120 different nationalities have been represented in the Premier League, making it arguably the world’s most cosmopolitan league with global appeal – currently approximately two-thirds of the players are foreign, with an even higher percentage of overseas managers and owners. It’s hard to imagine a time when a foreign player in the Football League was a rarity, or the intensity of debate as to whether they should even be allowed.

The history of the sporadic arrivals of players from around the world throughout the early decades of the Football League is outlined in the introduction to this series. The trend of occasional imports continued after the Second World War, with the prevailing attitude of the game’s authorities summarised by the Sporting Mirror headline of 1949, ‘Stop foreign players coming here’. One of the catalysts to ending England’s isolationist attitude to international football, which saw the FA shun the World Cup until 1950, was the famous shock of losing 6-3 at Wembley in 1953 to a Hungarian team with a much more sophisticated tactical approach. Followed by the advent of European club competition, there was a wider realisation that exposure to foreign teams and players might benefit English football.

By the 1960s, a change in attitude was shown by managers such as Stoke’s Tony Waddington advocating for importing top foreign players to the League. Writing in World Soccer in 1966 (‘Lift This Foreign Ban’), Brian Marshall expressed support for Waddington’s position, arguing that the addition of international stars to the English game could add “a little more colour and personality. It could easily prove a bigger attraction than it is today.” Marshall suggested “strict control” of imports but predicted their arrival “would lead to a big improvement in crowd appeal”.

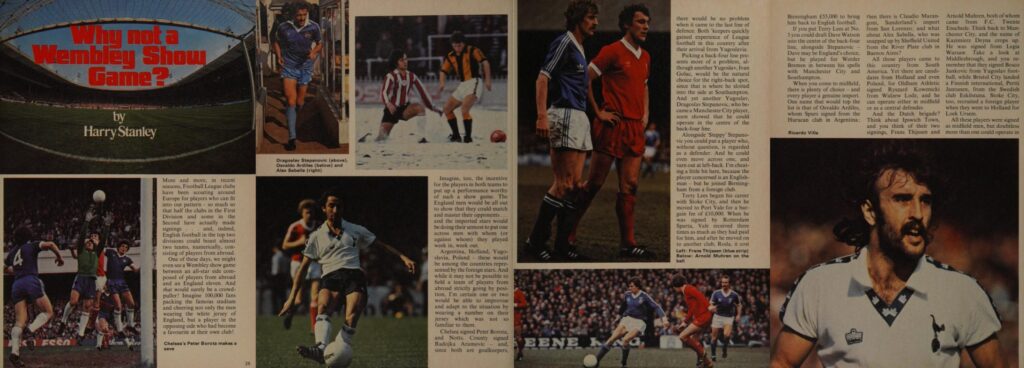

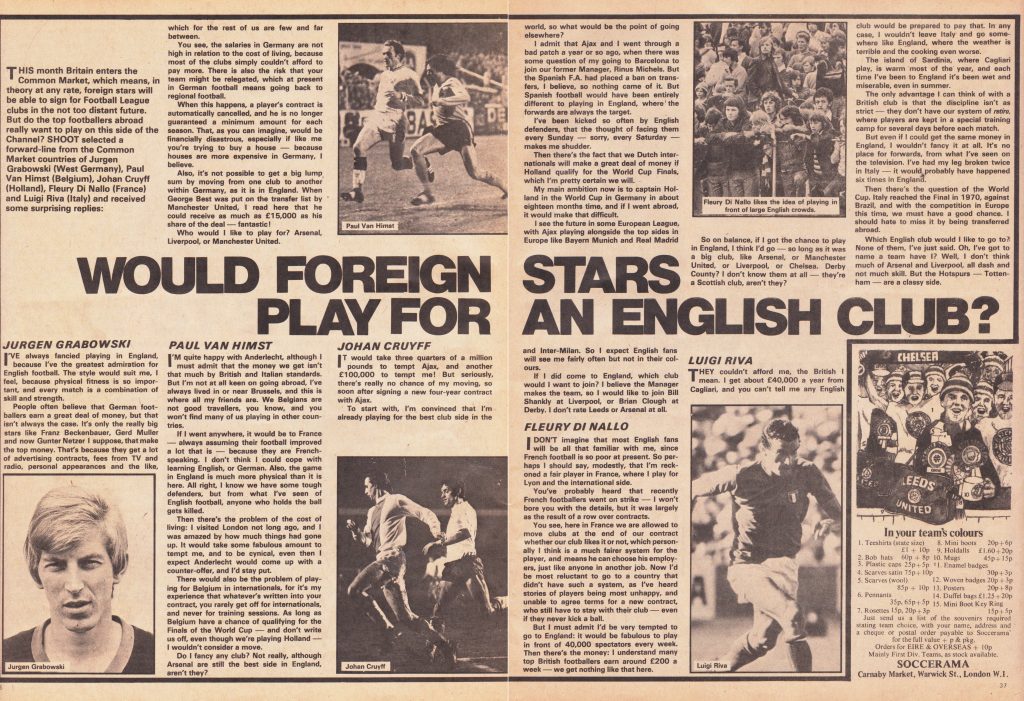

The debate on foreign players in England gained momentum in 1973, when the UK’s entry into the Common Market made it subject to the provisions of the Treaty of Rome (1957). This agreement enshrined the right for the free movement of workers within the European Economic Community. Although celebrated with a Wembley fixture at the time, among the future implications of the UK joining the EEC was that the Football League could no longer restrict the import of footballers from other countries. The League’s combative Secretary, Alan Hardaker, was an outspoken critic of the idea, declaring that allowing foreign players would “kill English football”. Shoot! magazine asked the question ‘Would foreign stars play for an English club?’ In Goal, manager Freddie Goodwin confidently predicted that ‘European stars will play in Britain’.

While negotiations continued in the European courts, there were increasing suggestions that English football was ready to embrace change. Brian Glanville, writing in 1975 (World Soccer), was in favour of bringing foreign players to the Football League though he suggested they be restricted “to one or two per club – personally, I would say one”. Glanville also warned that by allowing unlimited imports, “inevitably it must block the way to progress of the rising young native born players.”

By the time the provisions of free movement were fully ratified in the summer of 1978, English football was finally prepared for its first mass wave of imports. Bobby Robson, then in charge at Ipswich and later England manager from 1982, was in favour and reached the conclusion: “I think the advent of foreign players has been a good thing for football in this country and while they continue to have something to offer the game, they’ll keep coming in.”

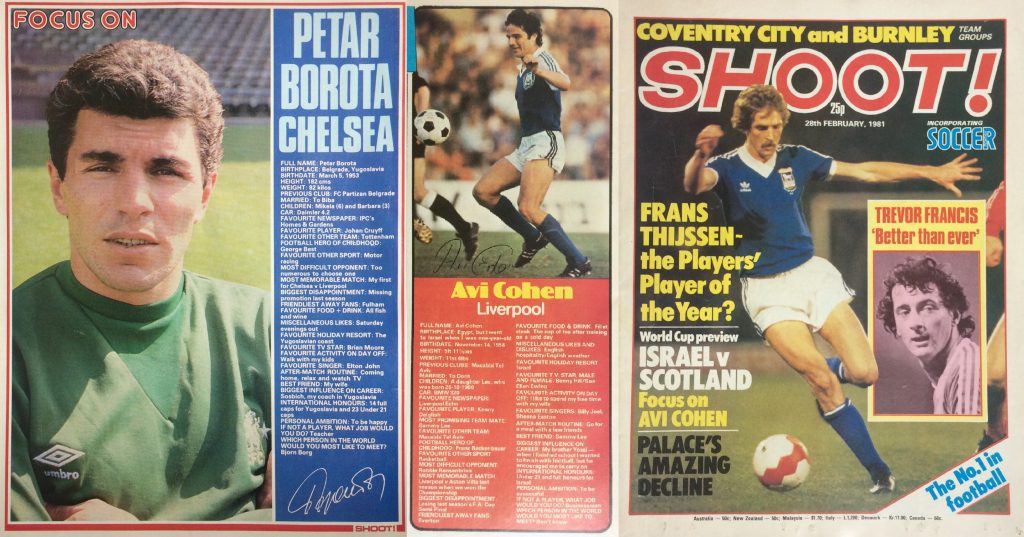

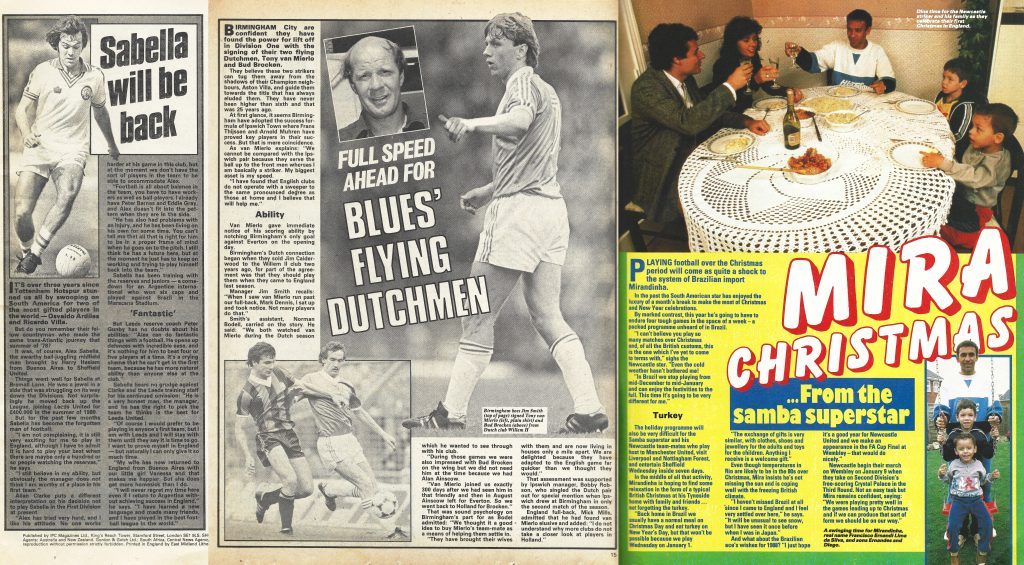

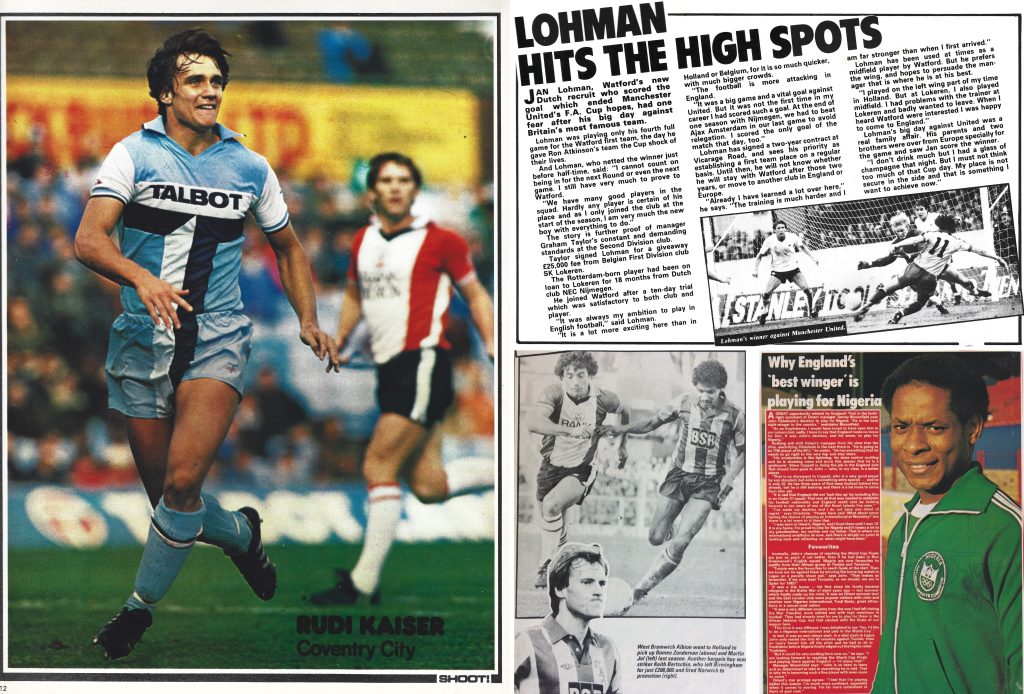

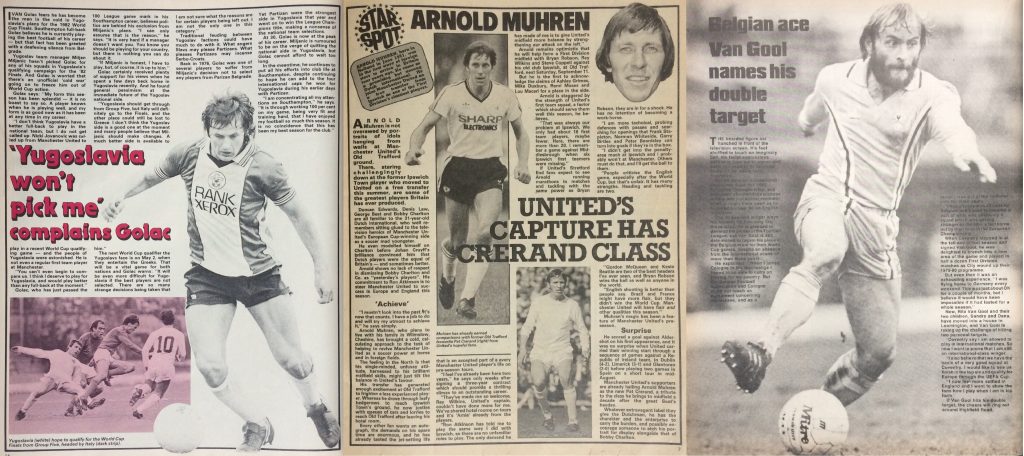

Robson brought Arnold Mühren and Frans Thijssen to Ipswich in the first batch of post-1978 signings, two of the most successful arrivals. Thijssen commented, “It’s a different game over here… Soccer’s much more exciting in England. The fans get a lot more entertainment than they do on the Continent. And as a player I certainly get much more enjoyment out of the game.” Norwegian Åge Hareide agreed that the Football League of the early 1980s was “much more physical than I was used to” but had “no doubt in my mind that it is the best in the world.”

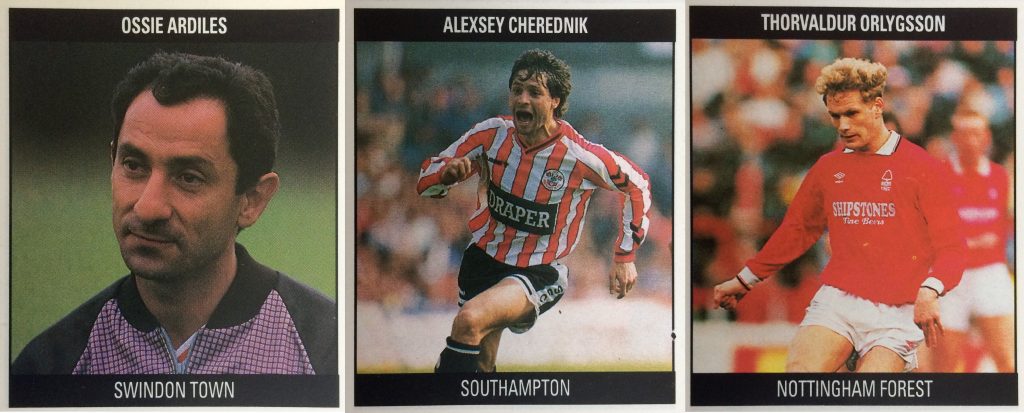

While Ossie Ardiles was another unqualified success, of course there were those who failed to adapt. Many of the foreign players who found themselves in the Football League between 1978 and 1992 made little impression. On the cusp of the Premier League there was still resistance to overseas signings with Gordon Taylor, chief executive of the Professional Footballers’ Association, stating as the 1990/91 season began: “I don’t want to put up an Iron Curtain in reverse but a lot of these imports are only being brought in because they are cheap”. Taylor and the PFA continued to advocate for restrictions until it became legally impossible.

After the Bosman ruling of 1995, the remaining barriers to freedom of movement for footballers fell and the effects have been seen across all European leagues – nowhere more than in English football’s top division. The change has been dramatic since Ardiles and Ricky Villa arrived at Tottenham in July 1978, with many factors contributing to the increase in numbers to the present situation where foreign players form a majority in the Premier League. The world of the 1970s was much different, more limited in terms of international travel and exposure to other countries. Even in the 1980s many talented players from across the world struggled to settle in England, on and off the pitch. Not only culturally but in playing style there was a big adjustment needed to adapt from South America to England at the time.

Worldwide television exposure has played its part in the differences of approach and tactics lessening as the game has become more global. The days when each country had its own identifiable style has disappeared with the movement of foreign coaches and players around the world. That ongoing process has made the transition of moving between countries more manageable, as has the ease of travel and a more cosmopolitan culture.

Another seismic change in the Premier League era has been the introduction of foreign managers (and later, owners). There had been only rare examples previously, with South African Peter Hauser the first when becoming player-manager at Chester in 1963. Arsenal and then Chelsea made bold approaches to Yugoslav Milan Miljanić in the mid-1970s; however the first non-English-speaking manager in English football was Uruguayan Danny Bergara, at Rochdale in 1988. Arguably the most successful playing import, Ardiles later managed Swindon, Newcastle, West Brom and eventually Spurs in the Premier League. Meanwhile Czechoslovakia’s Jozef Vengloš became the first foreign manager at the top level of the Football League when replacing Graham Taylor for a single season at Aston Villa in 1990. Not until 1996 was the experiment repeated with Arsène Wenger’s arrival at Arsenal, his success making him the pioneer for the trend toward foreign managers and gradually changing the face of English football.

This series of blog posts has included:

1. Introduction

& Appendix

4. Yugoslavia

& Appendix

5. a) The Netherlands (I)

6. Poland

7. Scandinavia & the Nordic Nations

& Appendix

& Appendix

10. North America

& Appendix

With special thanks to Nacho Dimari, Klaus Gallo, Jan Roskott, Mihajlo Todic and Jakub Drożdż (Polish Football Almanac) for their expert contributions. Thanks also to Peter Lythe, Miles McClagan (@TheSkyStrikers), Shahan Petrossian (Soccer Nostalgia) and the National Football Museum’s Collections & Research Centre for their assistance with research materials.

The history of foreign players in the Football League is one of the topics discussed in my book Before the Premier League: A History of the Football League’s Last Decades.