Yugoslavia: Foreign Players in the Football League

Yugoslavia provided a surprising number of imports to English football in the wave that followed the summer of 1978. While Ardiles and Villa, Mühren and Thijssen took the headlines, apart from the Netherlands no overseas country provided more players to the Football League in the immediate post-1978 period than Yugoslavia.

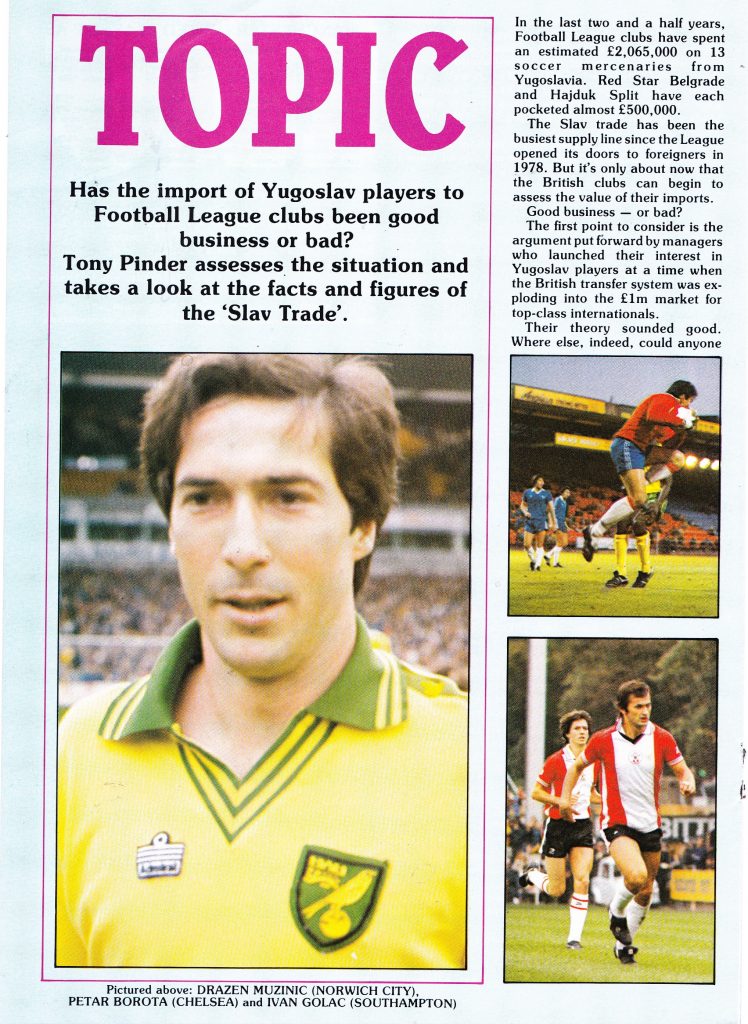

14 players moved to England between Ivan Golac’s arrival in July 1978 and Vladimir Petrović signing for Arsenal in December 1982. These two are arguably the most celebrated of a group of international footballers whose stays have often been forgotten or overlooked amongst more high-profile imports. Among the more memorable contributions by Yugoslavs in the Football League were Petar Borota’s eccentric goalkeeping at Chelsea, two goals from Middlesbrough’s Božo Janković to help deny Ipswich the league title in 1981, and Raddy Antić’s goal at Manchester City which saved Luton from relegation in 1983. Meanwhile established internationals such as Nikola Jovanović, Dražen Mužinić and Dragoslav Stepanović made little impression on the English game.

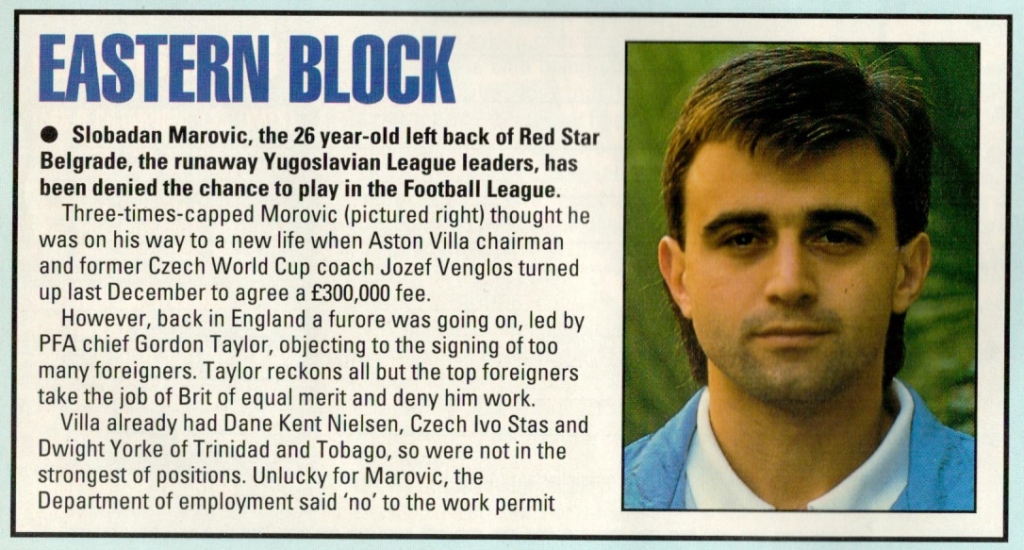

Several more transfers from Yugoslavia could not be completed because of the stringent conditions for work permits imposed after the first foreign players arrived in England during the summer of 1978. The criteria for issuing work permits was discussed in Parliament when Sheffield Wednesday tried (unsuccessfully) to sign Mojaš Radonjić, early in 1979. Among the moves to fall through was Sunderland’s attempted £250,000 record signing of Božo Bakota, the deal being cancelled after the player had already been photographed with club scarf alongside manager Ken Knighton. Work permit requirements continued to restrict imports even as Yugoslavia began to break up in the late 80s/early 90s – defenders Miloš Drizić and Slobodan Marović were denied transfers to Southampton and Aston Villa respectively.

The stream of imports from Yugoslavia was short-lived, with no player following Petrović for nearly ten years until Predrag ‘Preki’ Radosavljević arrived at Everton on the eve of the first Premier League season in 1992. Many players from the country’s former republics have since appeared in England from the 1990s on, including Igor Štimac, Slaven Bilić, Davor Šuker, Alen Bokšić, Saša Ćurčić, and Savo Milošević. However the dissolution of Yugoslavia as a nation in the early 1990s leaves the transfers of the trail-blazers over a decade earlier as a unique chapter in football history.

Serbian author and journalist Mihajlo Todić kindly took the time to provide extensive answers to my questions about individual players and the Yugoslav contribution to the Football League.

Interview with Mihajlo Todić

Q: Can you explain the background of the Yugoslavian Football Association’s policy concerning the transfer of players abroad in the late 1970s?

The rule of ‘28 years’ was applied in Yugoslavia. The football players could leave Yugoslavia only when they turned 28. Yugoslavia was a socialist state. For many years, sport was in line with the socialist system of the state. By the end of the 1960s, football players were officially amateurs. Football was not officially professional. The football players, however, made good money. They got money in various ways. In the late 60s and early 70s, football players began to receive the status of professionals.

In the early 1970s, clubs began to make rapid progress. The championship became very good. The stadium was full of spectators. State television and radio had special shows on football. The TV show “Sportski pregled” (“Sports Review”), in which reports from all matches were broadcast on Sunday evenings, was one of the most watched in Yugoslavia.

In such conditions, football players became stars. They were guests on TV shows, took photos for the front pages of newspapers, acted in movies, recorded music records…

All this was happening at a time when Yugoslavia was beginning to ‘turn’ towards Western Europe. At the same time, the state system was socialist. The government had to show the ‘ordinary people’ that football players are not a privileged part of society. They could not avoid going to the army for a year.

Men in Yugoslavia were obliged to do compulsory military service by the age of 28 at the latest. Only when they finished their military service could they get a passport with a validity period of 10 years. Strict regulations also applied to football players. The vast majority of players delayed going to the army almost until the last moment. The best players had to adapt to the needs of clubs and the national team.

I will give you an interesting example. In the qualifications for the European Nations’ Cup 1968 (Еuro ‘68), Yugoslavia played in a group with Albania and Germany. After the lost match against Germany, it was estimated that Yugoslavia would not qualify for the final tournament. Fahrudin Jusufi, Branko Rašović, Dragan Holcer and several other members of the national team went to the army. But, Germany played a draw in Tirana against Albania (0:0) and Yugoslavia advanced to the final tournament. Players who joined the army could not play in the Euro ‘68 in Italy.

I hope that with this long answer I explained that the transfer system in Yugoslavia was directly related to the policy of the Government of Yugoslavia. The football players were the entertainers of the people. They made more money than ‘ordinary’ people. They had great privileges. The price of privileges was to stay in Yugoslavia until the age of 28.

Robert Prosinečki managed to break the ‘28 years’ regulation when he transferred from Crvena Zvezda to Real Madrid. He was 22 years old. This happened in 1991, at a time when Yugoslavia was on the verge of disintegration and civil war.

Q: France and Spain had been popular destinations for Yugoslavs moving abroad. Why do you think so many players (14) came to England over the years after 1978?

It is interesting that Yugoslavia did not have great respect for English football. It is considered that in England they neglect technique and play strength football. It was also considered that the players from Yugoslavia play well in England because they have good technique.

People in Yugoslavia knew very little about football in England. Great respect reigned towards Liverpool and Manchester United. Liverpool’s visit to Yugoslavia in 1936 is remembered. Manchester United played great games against Red Star and Partizan. The tragedy in Munich in 1958 connected Belgrade and Manchester.

The departure of a large number of players to England did not change the situation. Even today, many people do not know who played for clubs in England. There were no reports of matches in England in Yugoslavia. Players going to England would be forgotten overnight.

I think the answer to the question about England as a popular destination is very simple. The football players knew the situation ‘on the field’ better. English football was more ‘open’ to internationals. Wages in pounds were higher and better than in French francs.

Spain was mostly closed to players from Yugoslavia due to political relations. At that time, there were almost no diplomatic relations between socialist (communist) Yugoslavia and fascist Spain (Franco’s rule). The departure of coach Miljan Miljanić to Real Madrid was a significant political issue. The coach from the socialist country went to the best club in the world and to the country of the fascist dictator. In the political sense, it was a great victory for Yugoslavia. Many years later, in Yugoslavia and Serbia, we realized how much Miljan Miljanić opened the door in Spain to our football players and coaches.

Q: Three of the players in England were goalkeepers – Avramović, Borota, and Katalinić – how were they regarded and would they have played for the national team again if they had stayed?

Take a look at the biography of the three goalkeepers and everything will be clear to you. None of them played for the national team after leaving Yugoslavia. At that time, players who played in Yugoslavia had the advantage of being elected to the national team. Those who left were considered too old for the national team. Losing the status of a member of the national team is the price they had to pay to go abroad.

Katalinić is the most respected. Katalinić was the goalkeeper of Hajduk from Split. Radojko Avramović was an excellent goalkeeper, but he defended Rijeka for the ‘small club’. In the ‘Adriatic rivalry’ (Split and Rijeka are cities on the Adriatic Sea), Avramović was in a subordinate position.

Petar Borota was an attraction. A goalkeeper who defended the impossible and conceded goals that a schoolboy would defend. The famous match between Romania and Yugoslavia (4:6) in the qualifications for the World Cup 1978 in Argentina. Borota was everywhere on the field except in front of his own goal. After that game, Katalinić was returned to the national team. Later, Katalinić was blamed for the lost game against Spain (0:1) in Belgrade in the qualifications for the World Cup 1978.

Borota was remembered for the goals he received in the match Partizan – Crvena Zvezda (Red Star). He conceded one goal by passing the ball through his legs. The second is one of the most famous goals in the history of the ‘eternal derby’. Borota seemed to stop the game, thought the referee had ruled a foul, and dropped the ball from his hands onto the grass. He moved away from the ball to rush to kick it into the field. Red Star player Miloš Šestić ran onto the ball and kicked it into the goal.

Various stories about Borota came from England. He allegedly sat on the crossbar during the match. According to another story, Borota defended a penalty in one game. The hat he was wearing fell into the goal, and he entered the goal with the ball.

Regardless of which clubs they played for and how good they were, Avramović, Borota and Katalinić ceased to exist for the national team when they went to England. The coaches of the national team had to show that there are still good goalkeepers in Yugoslavia.

Q: There were experienced internationals such as Dražen Mužinić and Dragoslav Stepanović – which of these players in the ‘first wave’ of transfers had the highest reputation in Yugoslavia?

The answer to this question depends on the side on which Mužinić and Stepanović were in Yugoslavia.

Mužinić played for Hajduk from Split and attracted more attention for the media in Croatia. Mužinić’s departure to Norwich City was great news for the media in Zagreb and Split. However, little attention was paid to the fact that Mužinić was the most expensive football player in the history of Norwich. I don’t think anyone mentioned that in the media. The bigger problem was who will replace him in Hajduk.

Dragoslav Stepanović is one of the best football players in the history of OFK Belgrade. His transfer to the Red Star was great news. Stepanović later moved to Eintracht Frankfurt. Believe me, the vast majority of journalists in Serbia do not know that Stepanović played for Manchester City. They were surprised to see this information on Wikipedia.

Q: Did the press follow the fortunes of these players in the Football League, or were they ‘forgotten’?

In Yugoslavia there were two sports dailies: “Sport” from Belgrade and “Sportske novosti” (“Sports news”) from Zagreb. There was also a sports weekly: “Tempo” from Belgrade. In each of these papers, it was only possible to find results or news from foreign competitions on one or two pages. All other daily newspapers had sports pages, but there was no place for news from foreign football.

We must, however, also understand what a time it was to live. The Internet, social networks and satellite television did not exist. The news travelled slowly. The only connection with the players abroad was the phone. It was very difficult for journalists to maintain contacts with players abroad. Texts and interviews with internationals were rare.

The press wrote much more about domestic sports. There were many topics. Basketball and handball were very popular and successful sports in Yugoslavia. Basketball players and handball players, men and women, were very popular, even more popular than football players. The handball national team won a gold medal at the 1972 Olympic Games. Partizan from Bjelovar won the handball European Championship 1972. Later, Metaloplastika from Šabac repeated that success in 1985 and 1986.

The basketball team won the world championship 1978. The basketball club Bosna from Sarajevo became the European champion 1978. Woman of Crvena Zvezda (Red Star) won the 1979 European championship. Cibona Zagreb won the European championship in 1985 and 1985. Water polo was half-steam, too. Boxing was one of the most popular sports. The boxers were very successful. Several thousand spectators came to the boxing tournaments. Ice hockey was well developed in Slovenia and Croatia. Footballers had a lot of competition in the fight for popularity.

At that time, there was another interesting phenomenon. Footballers often signed contracts for 10 years. The players stayed in the clubs for a long time. The transfer of players from one club to another in Yugoslavia was great news. It was talked about for days. They were real adventure novels. For example, Crvena Zvezda prepared the signing of the player’s contract in various hotels or houses. It was a way to prevent Partizan, Hajduk or Dinamo from trying to negotiate with the player.

Partizan had a different system of work. Partizan was founded by the Yugoslav Army. The club was run by army generals. A player who would accept to come to Partizan could postpone joining the army or get the opportunity to spend his military service in a city where there is a good football club where he could train. On the other hand, it happened that a player who did not accept Partizan’s invitation quickly received a call-up for military service.

Hajduk from Split has always been an interesting club. Split is the largest city on the Adriatic coast. Hajduk was a media favourite because of politics. After the Second World War, the work of all clubs founded before 1945 was banned in Yugoslavia. BSK and SK Yugoslavia were shut down in Belgrade. Partizan and Crvena Zvezda (Red Star) stadiums were built at their stadiums. Hajduk was the only one allowed to continue working and keep the year of its founding (1911). The name (“hajduk”, Turkish word for outlaw, forest robber who fought against the Turkish authorities in the Balkans. In Serbian, “hajduk” is a brave patriot who fought against the Turkish invaders) and the matches they played against the Partisan army, the patriotic army of Yugoslavia, helped them in that.

I wrote a little longer story to understand that the press had many interesting topics in domestic sports. At that time, the newspaper “Tempo” had a circulation of 700,000 copies.

Q: Božo Janković is one of the players who relatively little was known about before his arrival in England with Middlesbrough – can you describe his career?

He was born on May 21, 1951 in Sarajevo. Father Gojko was an officer of the Yugoslav Army (JNA), mother Nada was a housewife. He started playing football late, at the age of 16 in the juniors of Željezničar, one of the two big clubs in Sarajevo. Željezničar was a more popular club in Yugoslavia. It was a workers’ club. They founded the railway workers. Sarajevo was a so-called citizens’ club, so it gathered mostly local fans from Sarajevo.

Janković made rapid progress. He received an invitation for the youth national team of Yugoslavia (U-18). He signed a professional contract with Željezničar at the age of 17. He played for the first team in the 1968/69 season. He played forward and progressed quickly. In the 1970/71 season he scored 20 goals and was the top scorer of the championship with Pero Nadoveza from Hajduk Split. He was a standard member of the team that won the 1971/72 Yugoslav Championship. This is the greatest success in the history of Željezničar.

When he was 28, he received permission to go abroad. He played for Middlesbrough and Metz. Little is known about Janković’s career in England and France. At that time, Yugoslavia had a very good football league. It was considered that the First League of Yugoslavia was among the 6-7 best leagues in Europe. The stadiums were full of spectators and the players were stars. Players who played abroad were invisible. They could not play for the national team and the media would not talk about them.

After returning to Yugoslavia, Janković returned to Željezničar and ended his career. He played 265 games for Željezničar and scored 95 goals. Janković is the first player to score four goals against the Crvena Zvezda (Red Star) in Belgrade, at the stadium called ‘Maracana’. On May 2, 1971, Željezničar won 4:1. Janković was the scorer in the 5th, 10th, 17th and 29th minutes. After Janković, only one more player scored four goals against Crvena Zvezda at ‘Maracana’. It was Bayern striker Robert Lewandowski. Janković played only two games for the Yugoslav national team: the quarter-finals of the Cup of Nations – against the Soviet Union (April 30, 1972 in Belgrade and May 13, 1972 in Moscow).

At that time, Duško Bajević, center forward of Velež from Mostar, had the advantage. It is important that you know, Janković and Bajević are Serbs. Sarajevo and Mostar are cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At that time, the coaches of the national team made the team so that they had Serbs, Croats, Slovenes from various cities in Yugoslavia.

Janković was not a typical football player. He loved to read books. The graduation paper for his high school diploma was on the topic of literature. His favourite writer was Ivo Andrić, the winner of the Nobel Prize for the book “The bridge over the Drina”. He studied law and became a lawyer. He finished his football career in 1983. He remained in football for a short time as a member of the board of directors of Željezničar. When the civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina began, Janković had to leave Sarajevo as a Serb. He moved to Kotor – the city in Montenegro was a place where many Serbs left Sarajevo. He died on October 1, 1993 in Kotor.

Q: Dušan Nikolić was only 27 and had been highly-rated at Red Star Belgrade before joining Bolton, was he expected to move to a bigger club?

Dušan Nikolić came to Crvena Zvezda as a “pionir”, in the youngest category of players. He played for all junior selections and for another ten years for the first team (1970-80). He is a legend of the Red Star with such experience.

I will reveal an interesting detail to you. Nikolic’s nickname was ‘Staja’ (Staya). He was nicknamed after the English player Nobby Stiles, the famous Manchester United player. Nikolić was compared to Stiles in terms of style of play, they played in the same position. The teammates translated the witty name of the English football player to Staya. The nickname was the biggest award Nikolić could receive. There were better football players in the Red Star and in Yugoslav football. Nikolić was a worker, in Serbia we say “water carrier”.

Because he was not an attractive player, he was allowed to leave Yugoslavia at the age of 27.5. Nikolić’s departure to Bolton did not provoke any reaction from fans or the media. If there was no talk of Liverpool or Manchester United, all other English clubs were equally unknown in Yugoslavia.

Q: Ante Mirocević had been a key part of the 1980 Olympic team, he also joined a team at a lower level and played in the Second Division with Sheffield Wednesday. How was he viewed in Yugoslavia?

Ante Miročević was one of the most popular players in Yugoslavia. One of the reasons is that he played for Budućnost from Titograd (today Podgorica). Budućnost (translated as ‘Future’) was the best club from Montenegro. Budućnost was never at the top of the First League. They played twice in the finals of the Yugoslav Cup. Miročević is the first player from the club from Montenegro to play for the Yugoslav national team. He played many more games for the Olympic team than with the A team. He was thus considered a member of the ‘B selection’.

All big clubs from Yugoslavia tried to sign the contract with Miročević. Nobody succeeded. He played only for Budućnost. He moved to Sheffield Wednesday for 150,000 pounds.

This is an interview that Miročević gave in 1980 for the newspaper “Tempo”.

“During the negotiations with Sheffield, I was Jackie Charlton’s guest at his house. I was received at the club as if I had been their member for 100 years. It is an honor for everyone to play in the cradle of football, even in the second league club. In England, there is not much difference between the first and second leagues.”

Miročević was reprimanded by the then national team coach Miljan Miljanić on his departure to England. “I do not see the reason for Miljanić’s anger. I have fulfilled the conditions for going abroad. A favourable oportunity came to me. Should I have turned it down? The contract with the new club includes a clause that I can play for Yugoslavia at any time. I will now prefer the invitation to the national team more than any previous one.”

Miročević thanked the management of Budućnost for allowing him to go to England.

“The management of Budućnost was very correct, they understood my desire to leave, although they were not obliged to do so.”

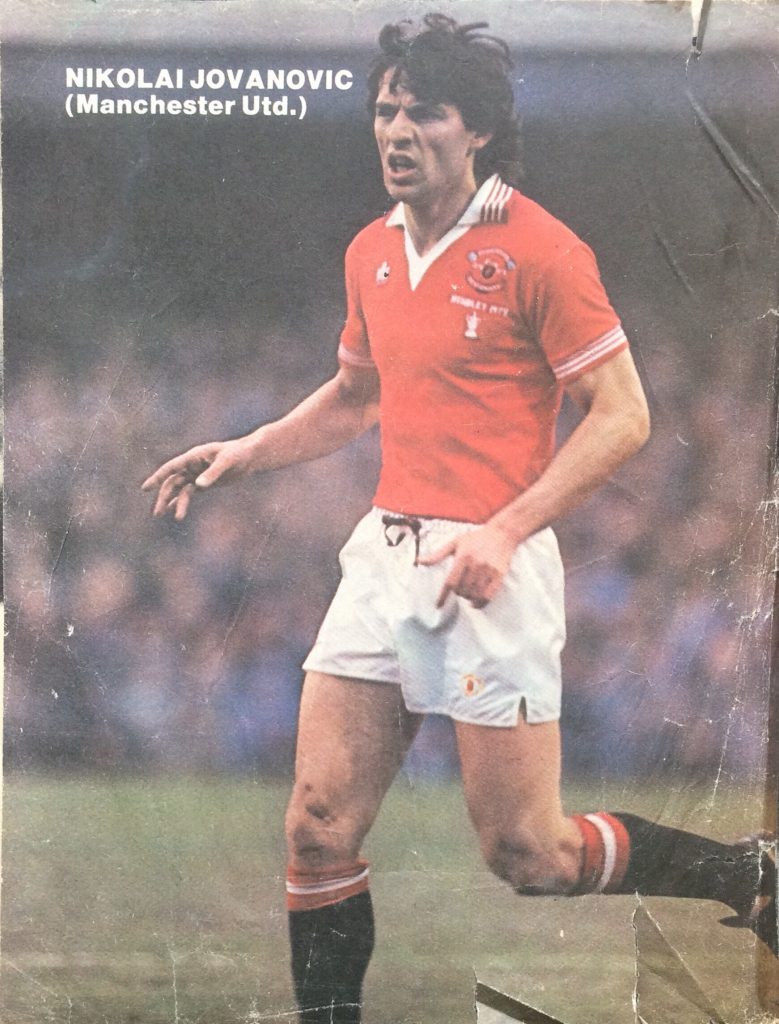

Q: The player who joined the biggest club was Nikola Jovanović at Manchester United – he was included in the 1982 World Cup after returning to Yugoslavia. What was his reputation and did it suffer from his short spell in England?

It is interesting that Jovanović is a Montenegrin, as is Miročević. He played for Buducnost, as did Miročević. He was 23 when he came to the Red Star.

The departure of Nikola Jovanović from the Red Star to Manchester United was great news. The press emphasized that a great honour had been done to Yugoslavia. It is stated that Jovanović is the first football player from the continent of Europe (outside the British Isles) to sign for Manchester United. Jovanović personally previously refused the invitation to move to Bayern Munich. This is perhaps a good example of how much Manchester United was respected in Yugoslavia. That is the reason why the press occasionally wrote a little more about Jovanović. The question was mostly asked why Jovanovic played few games for Manchester United. The explanation was usually a back injury due to which Jovanović ended his career at the age of 31.

This is part of an interview that Jovanović recently gave to a Serbian newspaper:

“I had many offers. The most popular was Bayern Munich, but I was attracted by Manchester United, England, island football… The transfer was 350,000 pounds at the time, that was a lot of money. I was the first and only foreigner in the club. It was unusual and difficult, but I prefer to remember beautiful things. I will never forget the fans. There were always 50,000 spectators in the stands and the only thing that mattered was that you did your best. Nobody is like Zvezda, but I also see Manchester [United] as my club and I am looking forward to success. Now there are more foreign than domestic players there”.

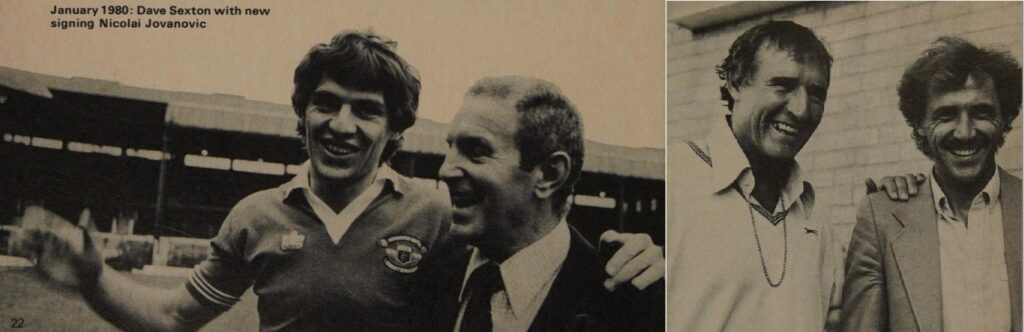

Above: Nikola Jovanović with Dave Sexton; Malcolm Allison with Dragoslav Stepanović

Q: Vladimir Petrović was probably the biggest star to move to England when he joined Arsenal at the end of 1982. What was the reaction to his transfer, and how was his time in England later viewed by fans and press?

Petrović’s transfer from the Red Star to Arsenal was the news of the year. Petrović was supposed to move to Arsenal in July 1982. That year, Yugoslavia played at the World Cup 1982 in Spain, and Petrović had not yet turned 27. The Yugoslav authorities did not allow Petrović to go to Arsenal earlier. The Football Association of Yugoslavia organized a vote of members of the leadership on whether to allow Petrović to go to England earlier. Out of 16 members, 9 voted “no”. Petrović believes that he was punished for the failure of the national team at the World Cup 1982, where he was the best player in Yugoslavia, along with Ivan Gudelj.

This is part of an interview that Petrović recently gave to the Serbian media.

“After the failure at the World Cup in Spain, everyone was angry, and I paid for the guild. It was the Serbian staff in the FS of Yugoslavia, therefore, President Tomas Tomašević and Vinko Jamnik, who voted against me. It was very difficult for me, but there was no one to protect me. I went to Arsenal after half a year, but for much less money. My contract was £700,000, plus salary. At that time, 10 percent went to the club and 10 percent to the manager, the rest would go to me. When I arrived at Highbury with such a delay, I played for £40,000. I left after six months. The main reason, in addition to the fact that English was played and that I could not get to the ball, is certainly the fact that they paid me a little. So after six months, they told me: ‘It’s easier for you to leave than to change 10 players.’ They were, of course, right. I admit, Arsenal is my angry wound, because if I had stayed longer, I would surely have made a great career on the Island as well.”

At the end of 1982, at the age of 27.5, Petrović received a special permit to go to Arsenal. Petrović loved English football very much. He liked to play against English clubs. He was an excellent technician and he believed that he would delight Arsenal fans in matches against strong opposing players. Most of all, he loved the white ‘Mitre’ ball. Even today, he says that ‘Mitre’ is his favourite ball.

Petrović’s quick departure from Arsenal was considered a great failure of a great football player.

Q: What were the reasons that the steady stream of transfers from Yugoslavia to England stopped by the middle of the 1980s?

I think the cessation of players leaving Yugoslavia for England is a combination of several causes. After World Cup 1982, a big change was made in the work of clubs and national teams. Several younger players played. Young people had to wait a long time for permission to go abroad.

Another reason is quality football in Yugoslavia. The period 1982-90 is remembered as the “golden age” of club football in Yugoslavia. Great changes were made during that period. Players are allowed to become professionals. They got apartments, cars, a lot of money for the contracts.

At the same time, England was notorious for hooligans. The suspension of English clubs from European competitions probably affected the need for English clubs to hire foreigners. At the same time, the unsuccessful adaptation of Jovanović and Petrović to English football influenced the players’ desire to play in the biggest clubs.

It was at that time that France, Italy and Turkey ‘opened up’ to Yugoslav football players. Few players who have acquired the conditions to go abroad gladly chose to stay in the south of Europe. The best went to France and Italy, but those who went to Turkey earned more money.

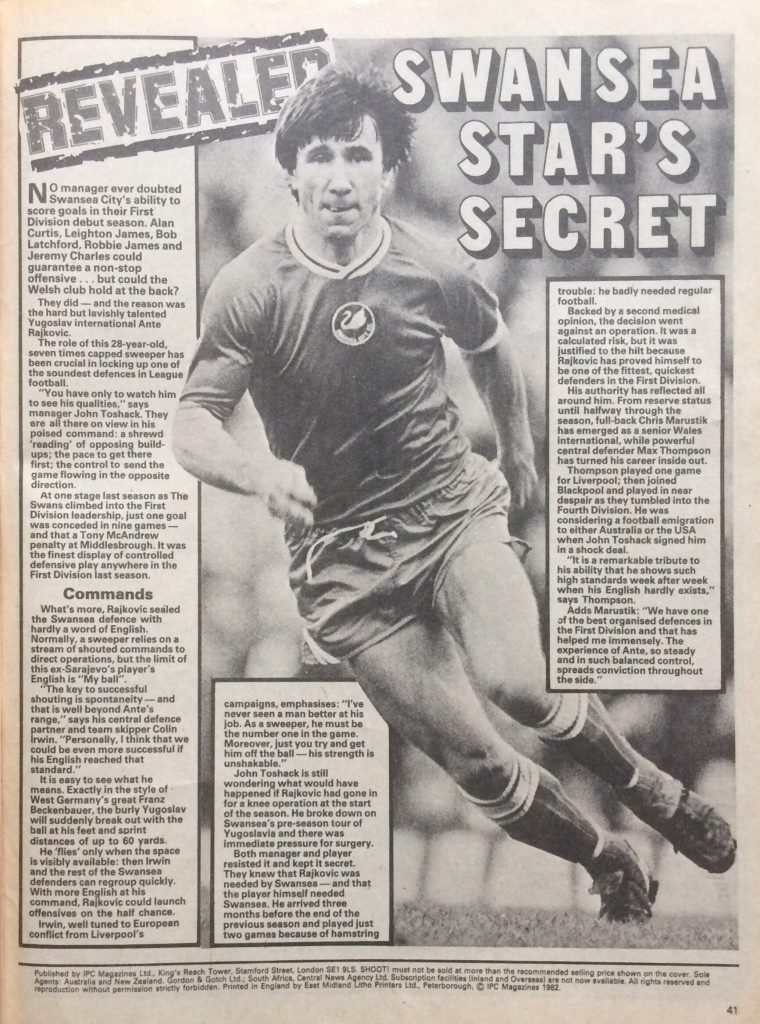

Q: Finally, many of these players we mentioned did not make an impression in England and only stayed a short time. Some of the lesser-known players adapted better – Avramović, Golac, Hadžiabdić and Rajković at Swansea. Why do you think top-quality international players struggled in the Football League?

I think that the players from Yugoslavia were not well enough prepared for English football. The style of play was a problem for many players. Football in Yugoslavia was different from what they played in England.

Another problem was habits. The football players in Yugoslavia trained a lot. They usually had two workouts a day. Despite that, only one training session a week – and that was usually on Tuesdays – was dedicated to fitness. The other days were dedicated to training on improving technique. I believe it seems amazing to you, but the method of work was mostly the same in all clubs.

Non-adaptation to professional football was a big problem. The players in Yugoslavia had everything organised: when they get up, when they have breakfast or lunch, when they go to sleep. Football players in Yugoslavia did not have to think much about how to spend the day.

In England, the small number of players who understood what professional football is, did better. I am often in contact with Ivan Golac. We hang out as a family. Golac behaved like a professional football player while he was still playing for Partizan. Players like Golac were considered ‘strange people’ in Yugoslavia. So it is today.

A huge thank you to Mihajlo Todić for the time he took to provide such thorough answers for this feature. Mr Todić is a writer and editor of the international football section of the Sportski žurnal, with a keen interest in English football. His books include Antologija Svetskog kupa (Anthology of the World Cup, 1998), Kontinent fudbala (Continent of football, 2000), Treći vek fudbala (Third century of football, 2002), Sto godina romantike (One hundred years of romance, 2011) and Kako je fudbal porastao? (How did football grow?, 2016). He is on twitter and also has a blog focussing on football history.

Several images courtesy of Miles McClagan: Flickr & twitter @TheSkyStrikers

The arrival of foreign players to the Football League at the end of the 1970s is one of the topics discussed in my book Before the Premier League: A History of the Football League’s Last Decades.