1930 World Cup: Anniversary of the first finals

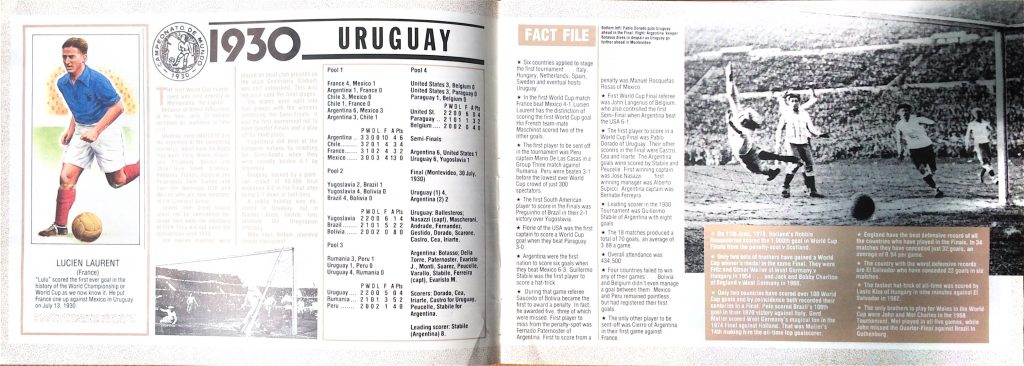

July 2020 sees the 90th anniversary of the 1930 World Cup finals, hosted in the Uruguayan capital, Montevideo. Instigated by FIFA President, Frenchman Jules Rimet, thirteen nations accepted the invitation to compete in the historic first tournament. Four of the squads made the arduous trans-Atlantic crossing from Europe.

The opening two games kicked off simultaneously on 13 July 1930, France-Mexico and USA-Belgium – at the Estadio Pocitos, France’s Lucien Laurent made history by scoring the competition’s first-ever goal. Four days later, USA forward Bert Patenaude recorded the tournament’s first hat-trick against Paraguay. The four group winners – Uruguay, Yugoslavia, Argentina and the USA – progressed to the semi-finals. Both South American countries went through with 6-1 victories, though Jim Brown’s late goal for the USA means he remains to this day the only American (and Scot) to score in a World Cup semi-final. On 30 July, the final took place at the 93,000-capacity Estadio Centenario, as hosts Uruguay recovered from 2-1 down at half-time to beat Argentina 4-2 and become the first nation to lift the Jules Rimet Trophy.

These are the main facts of the first World Cup finals, placed in the history books for posterity. Yet as the years go by, there is a risk that is where the tournament will remain, as living memories are lost. Among the historians trying to prevent Uruguay 1930 disappearing completely into the mists of time are James Brown, grandson of semi-final goalscorer Jim, and Dean Lockyer. Their research has crossed Continents from the USA and Europe to encompass a worldwide search for descendants of players in the first finals, preserving memories from nearly a century ago, uncovering contemporary reports and memorabilia. I had the opportunity to ask them a few questions about their 1930 World Cup Project.

Can you just explain a little about the background to the tournament and the nature of international football at the time?

FIFA asserted the right to organize an international tournament in its founding constitution in 1904. But the infrastructure and quality of football on the continent and elsewhere was nowhere near the level with the inventors of the game in the British Isles. The gradual growth of the game globally and improvements in transport infrastructure, encouraged competition among neighbouring states on an inter-club and inter-regional level. The growth of the Olympic games was instrumental in providing the platform of encouraging international football among nations from further afield. The Olympic football tournaments of 1908 and 1912 were an early example of this, as the nations of Britain, Scandinavia, continental Europe, and Russia competed. In 1920, Egypt was the first nation from outside Europe to compete at the Olympic football tournament and also participated in the next two editions. This is when the Olympic football tournament became a truly intercontinental competition, as nations from Uruguay, USA, Argentina, Mexico, Turkey and Chile contested for medals against increased European participation in 1924 and 1928.

The introduction of inter-regional tournaments furthered the process and increased competitiveness. Britain had its own ‘Home’ championship as early as the 1880s and a South American Championship was first played in 1910. Japan, China and the Philippines were competing at the Far Eastern Games as early as 1913. But it wasn’t until the 1920s that such tournaments became more common with the creation of Cup competitions in Scandinavia, the Baltics, the Balkans and the Mitropa Cup for nations in Central Europe.

The logistics and travel arrangements presented a challenge – do you have any stories of how the different nations actually got there?

The World Cup was created as a competition open to professionals and amateurs, all arising because of the issue of ‘broken-time’ payments to amateurs taking part in the Olympics. But with the competition held in far-off Uruguay, this caused issues for both factions. Clubs were not prepared to do without their players for a trip that would last two to three months as it would interfere with the beginning of the season. This was the case in countries such as Austria and Spain. The amateurs would struggle to get time off work for such a period, especially if it meant going without pay and this was particularly true in the Netherlands.

Mexico had the longest journey of all the nations that took part. They left Veracruz on June 4th and headed north-east to Havana and then on to New York where they stayed for a few days before leaving on the Munargo with the US team. The boat headed south with stops in Bermuda, Rio and Santos before arriving in Montevideo July 1st. It was 26 days for the Mexicans and 18 for the US.

The Belgians left Brussels for Paris on June 20th but instead of heading to the South of France to catch the Conte Verde with the French they travelled to Barcelona where they joined the French and Romanians. They arrived in Uruguay on July 5th, a fifteen-day journey.

Yugoslavia left Belgrade by train on June 17th and made their way through Austria and Switzerland before boarding the English liner Florida in Marseille. There is some evidence they did not want to travel on the Italian liner, the Conte Verde, because of diplomatic disputes with Italy over the Adriatic coastal city of Trieste. They arrived in Montevideo on July 7th, twenty days after leaving home.

It took the Peruvians 11 days to get from Lima to Uruguay. Travelling by boat they made up to three stops on the Chilean coast before taking the train from Valparaiso across the Andes to Buenos Aires, where they crossed the River Plate to Montevideo.

Travelling by boat restricted all the teams training to a purely fitness-based regimen.

The Bolivians were last to arrive in Uruguay. The border town of Villazón, which the Bolivian team would cross into Argentina, had been overtaken by Communists in late June. The government retook the town a few days later, but then a popular revolution broke out in the capital, La Paz, against President Siles who had attempted to violate the constitution to run for a second term. The main army battalion that rebelled against the government was based in the tin-mining city of Oruro, where the Bolivian team had set up their training camp. It wasn’t safe to travel. The President was quickly overthrown and the Bolivian team arrived in Montevideo on July 11th, two days before the start of the World Cup!

Who were the star players and main personalities of the tournament itself?

In the Uruguayan team there were an array of stars such as captain Nasazzi, Andrade, Lorenzo Fernández, Scarone, Cea and Petrone, who had led the country to Olympic glory. Pedro Petrone disappointed in his first game against Peru and was later dropped while the legendary José Leandro Andrade was perhaps past his peak. However, he made a vital block in the final to prevent Argentina from scoring an equalizer with Uruguay leading 3-2 before Héctor Castro scored the fourth in the final minute. Héctor Scarone was making his last appearances for his country and his exquisite overhead lob set up Pedro Cea to score the equalizer in the final. It was the leadership of José Nasazzi that would lead his country to glory. His half-time team talk inspired a second-half comeback with the team trailing 2-1. Pedro Cea playing at inside-left had a decent goalscoring record playing for his country, but he never had such a goal-scoring streak as his five goals in four games during the World Cup.

In the Argentinian team, Luis Monti, Manuel Ferreira and Juan Evatisto were the star men. As, too, was Roberto Cherro, the Boca Juniors attacker known as ‘Cabecita de Oro’ (the Golden Head) because of his aerial ability. But as we shall see he had a disappointing first game and would play no further part. But it was Guillermo Stábile who would emerge as the star of the team. He got his opportunity in Argentina’s second game against Mexico when striker and captain, Manuel Ferreira returned to Buenos Aires to take a law exam. He hit three against the hapless Mexicans and would finish the tournament as the top scorer with eight goals.

It would be appropriate to highlight the goalscoring feats of US striker Bert Patenaude who scored four goals in three games, including the first World Cup hat-trick against Paraguay. Also worthy of mention are two goalkeepers. Alex Thépot performed miracles in France’s 1-0 defeat to Argentina and he was unlucky to concede Monti’s free-kick when he was unsighted by a disorganised French wall. Milovan Jaksić was a stalwart in the Yugoslav goal in his country’s shock 2-1 victory over the seeded Brazilians. He was christened “El Gran Milovan” by the South American press for the 30 shots he kept out. Both keepers were the subject of interest from photographers after their performances.

Were there any controversial incidents during the finals?

Most involved Argentina and Luis Monti, the Argentinian centre-half: Argentinian team bus attacked after the France game; Monti creates a disturbance with opposing fans during the Mexico game; Monti sparks a brawl vs Chile; controversial goals awarded during Uruguay vs Yugoslavia; death threats to Monti prior to the final; riots in Buenos Aires afterwards.

I was pleased to find that two of the three stadiums used are still standing – is the legacy of 1930 generally well preserved in Uruguay?

Regardless of the 90 years that has gone by, there is a real strong sense of history and importance in preserving and educating the world, now more than ever. Uruguayan historians like Atilio Garrido, Sergio Gorzy, Pierre Arrighi and many more work to properly research and preserve history, much like author Aldo Mazzuchelli’s book “Del ferrocarril al tango: El Estilo del Fútbol Uruguayo, 1891-1930” (From the railway to the tango: The style of Uruguayan football, 1891-1930). Also, filmmakers Facundo and Juan Ponce de León investigate and set the correct order of Uruguayan football’s origins with their three-part documentary “El Origen” (Aldo Mazzuchelli wrote the script) and the World Cup’s rich history. At the league level, Montevideo’s Nacional Club’s historical society works just as hard to unearth and document the World Cup’s history, as the original idea to host the World Cup came from the club’s directors José Gervacio Usera Bermudez and Robert Espil.

In Argentina, historian Esteban Bekerman and other groups such as Historia AFA work towards the same goal as Uruguay. With collaborative efforts on an international level, South American FA and club historical societies often work with the Society for American Soccer History (S.A.S.H.) to help answer and clarify stories, flesh-out ideas and double-up research efforts. There is a very rich exchange over the past years between historians, writers, authors and passionate researchers like us. We’ve established great connections with South American “Keepers of the 1930 World Cup”. The great thing is that from all parts of the world; EU, US, Central America – there is great understanding and excitement for the importance that the 1930 World Cup has on today’s national team and even a country’s pride.

Football is a federator, crossing over even the darkest moments from a political perspective.

All of these examples above often filter into the expansive online resources and social media networks, like Twitter, where Dean and I interact with this vast international group of individuals and societies who take a personal interest in making sure the 1930 World Cup is properly represented, from all of the thirteen nations that participated.

What are some of the most significant finds you have made in your research, in terms of memorabilia and memories?

In the beginning of the research, my association with Esteban and Aldo allowed me to have a 360° view of the US team from media in Argentina and Uruguay. I was often touched to hear that the media felt that the US was progressively getting stronger and stronger because of their sheer determination to make their mark on the first championships, after having experienced a mediocre past ten years at the Olympics but having the opportunity to battle against British First Division teams. Also, the US team was very tight-knit and was appreciated more and more by the Uruguayans and South Americans as a whole.

What are your plans to commemorate the anniversary of the first World Cup, and how do you see the project progressing in the future?

During July 2020, I’m working with a great group who want to ensure that the 1930 World Cup shines on the international level during the 90th anniversary. Local events will be held by top-flight clubs in Montevideo and Jules Rimet Project 1930, and on a virtual social media level through Twitter with 1930 World Cup Conference, with recorded interviews talking about specific matches or national team perspectives from specific FA historians, journalists or authors, World Cup 1930 Project and my account, 1930 World Cup – and countless others on a daily basis. More events will be planned during the year and then following up in late March 2021 with a conference that will tackle a wide range of topics that range from the 1930 World Cup: revisiting key personalities like Jules Rimet and Enrique Buero, Sr. to issues that affect today’s game, like VAR or women’s rise in football on all levels of the game, with expert speakers and panellists.

With many thanks to Dean and James for their expansive response to my questions.

Contact details:

James’s Personal Twitter: @1930WorldCup

Dean’s Personal Twitter: @WC1930blogger & www.worldcup1930project.blogspot.co.uk

Conference Twitter: @1930Cup & http://www.worldfootballconference.com