Derek Goodier: An Interview (Part Two)

The second part of my interview with Derek Goodier moves onto football from the 1960s onwards, and explores some of the main differences between ‘then and now’.

Over the years from the fifties into the sixties, my impression is that there were less goals scored, the game became a bit more tactical and defensive. Was that your experience of watching it over the years, did you notice a change coming into football?

Yes, I watched a decline in the skills aspect and the goals scored. At one period if a team scored four goals, you’d think that you could score five. It’s all geared up now for ball possession which doesn’t mean a thing. If you have 23 possessions and you score a goal and win 1-0, what is the good of possession? It’s what you do with the ball. If you’ve got a ball, as they do now and you play it across the field all the time, it goes backwards because nobody has the nous to go forward and do something out of the ordinary – to take somebody on or a forward with the guts to run and ping in with the ball. It’s been knocked out – we play the Continental method which is possession, which is a South American thing as well. Possession isn’t 90% of the game, it’s only one little aspect of the game. If you do nothing during possession – pointless.

Which were your most memorable matches of that era?

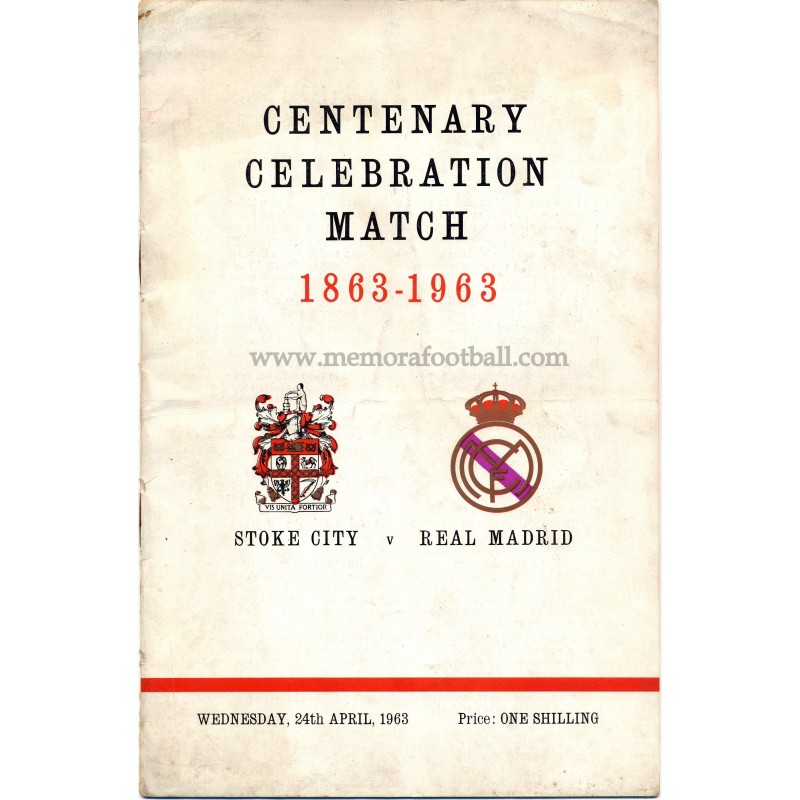

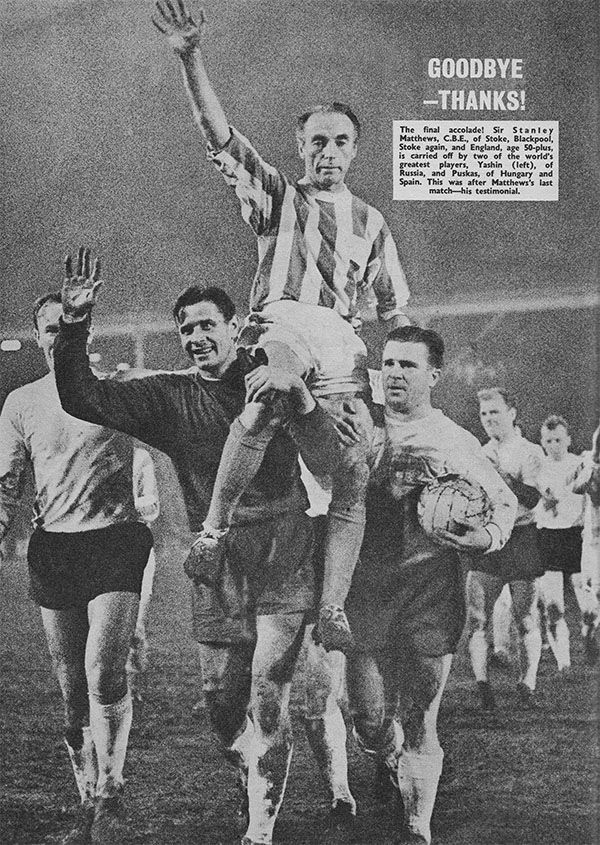

I went to Stan Matthews farewell match at the Victoria Ground [Stoke on the 28th April 1965] – it was packed. The opposition was a world squad of players including Ferenc Puskás, Alfredo Di Stéfano, Lev Yashin, Jimmy Greaves, Johnny Haynes, Jim Baxter, Cliff Jones and a host of elite players. Stan was carried from the pitch by Puskás and Yashin. Then there was Stoke’s Centennial match [played at the Victoria Ground] in April 1963 against Real Madrid, the Spanish Champions, who came with their full team – Di Stéfano, Puskás, Gento and all the rest of the stars. The match ended 2-2 and before the game there was a match involving all the old players of the 30s and 40s. There was also a friendly against Santos with Pelé in 1969. Some great players.

Stanley Matthews Farewell Game 1965

What are your memories of the 1966 World Cup – did you go to any of the games? What were your impressions of that tournament?

I thought we were extremely lucky to get through at one point. When Rattin was sent off for Argentina I thought it was very lucky to get through that match. If anything we should have lost it. I went to one match, England didn’t play in it – it was [North] Korea and Portugal at Goodison Park. The football there wasn’t bad, it was Eusébio now I think about it, yes it was. He was a phenomenal player that bloke, a big lad. You didn’t knock him off the ball. He was a nice player, very nice player. But he was a bit like Ronaldo is now with Portugal, he was the player. There was nobody else. A one-man team. That man could carry them, he was brilliant.

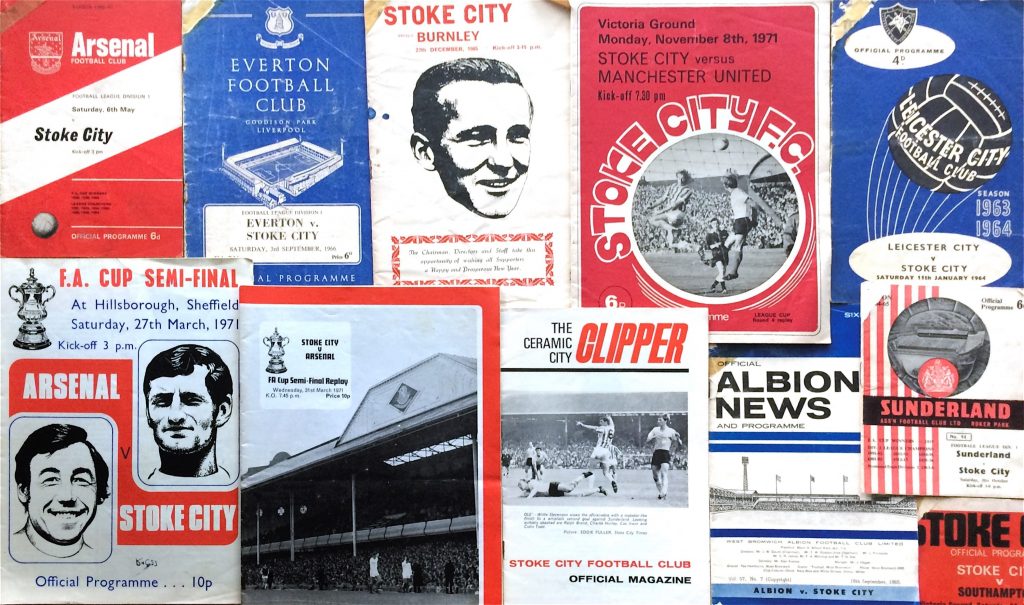

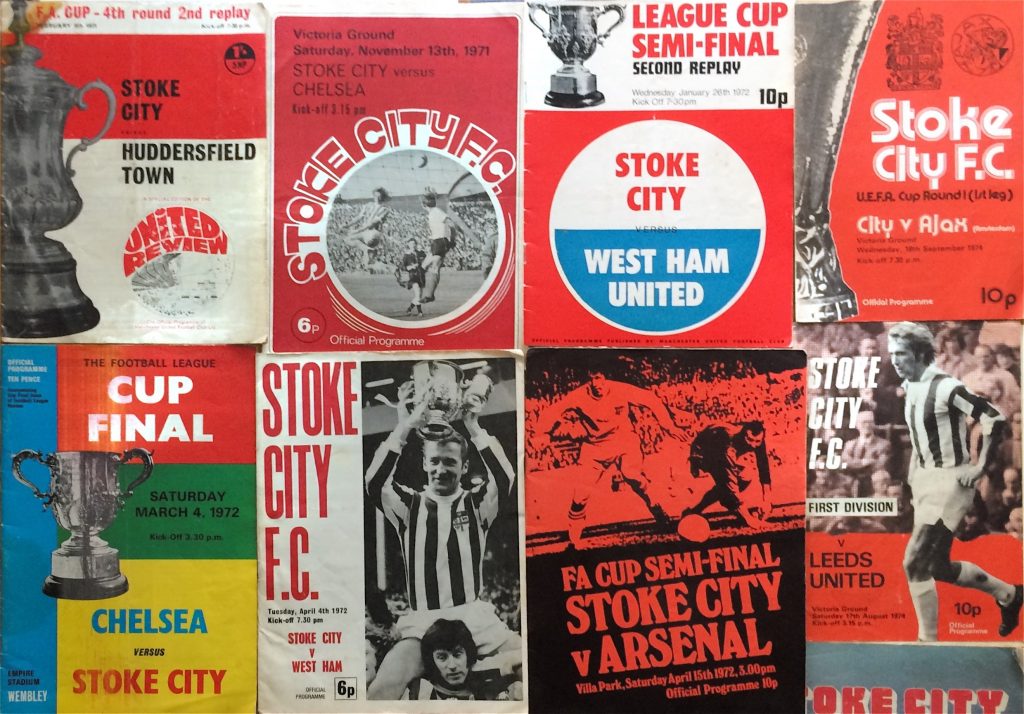

Just returning to Stoke, they had earlier success and they’d had Stanley Matthews but towards the late sixties/early seventies they had a successful First Division team, won the League Cup. What are your memories of the Stoke team around that period?

They were a fantastic team. They’d got Gordon Banks in goal which was worth, well worth anything, he was the best goalkeeper I’d seen in my life. They had a good defence, a brilliant defence, and a forward line that was equal to anything. They could play your Manchester Uniteds and all of them off the pitch. They were a real, real good side. And the thing was, the man who made them was a bloke [Tony Waddington] who’d only ever played for Crewe Alexandra in the reserves. He was no great footballer which just goes to show you that you don’t have to be a phenomenal footballer to be a good manager. You’ve got to know what you are talking about and what clicks together – that’s what makes football, not top names going into management.

That team went a little bit into decline and football changed again around the time that I was a kid [late 70s/early 80s]. The crowds were falling and there was more hooliganism around. Did you have any experience of that? You were still going regularly to games around that time.

I was going, yes. You’d get hooliganism, it was part of the game. It spoiled football. A lot of people stopped going because of the violence, they wouldn’t take their children because of the violence and language. It wasn’t just on the pitch or in the stadium, it was outside as well. It was just rife with it. They had to do something with hooliganism but it will never return to how it was I don’t think.

While we are on the 1970s in particular, I just wanted to ask you about a couple of the personalities and teams at that time. George Best for number one?

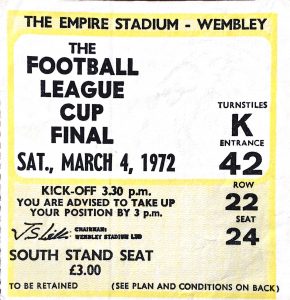

Phenomenal player. I met George Best in the hotel where we stayed for the League Cup Final [in 1972], Manchester United were there. I was chatting to him – he was only a small little frail person, you’d wonder how he stood up to all the battering he got. He was nothing really, probably about 9 stone wet through. I asked him ‘would you sign my programme George?’ ‘Oh yeah, no problem’. He was amiable, a nice bloke, very nice bloke. [his problem was] Drink, which killed a lot of footballers all through the ages. You can’t drink to excess and play football, there’s no way you can do that. You’ve got to be clean of body and clean of mind to play football. You need to have a fast brain and a clean body otherwise you are found out.

George Best’s autograph on reverse of 1972 League Cup Final ticket

That era was the first time that the managers became a big personality in their own right, maybe more than the team in some cases – so Brian Clough, I presume you also knew him as a player as well as a manager. What are your thoughts on Brian Clough?

Brian Clough was a good bloke. He was a bit too brash for the management of England or any other place. I think they accepted him at Derby and they accepted him at Nottingham, but there was no way he could have walked into a Southern side and managed a Southern side. At Leeds they didn’t like him because he was too brash, but as a footballer and a goalscorer very few equalled him – he was so fast, so brave and as a positional player he was unbelievable. He could get into position and that’s part and parcel of being a goalscorer. It’s no good being up there, you’ve got to be in the exact position and that makes a centre-forward, and yes he was a good player. A good manager as well. He knew what he wanted and if the person that he had there didn’t produce what he wanted, then he went by the wayside until he found the person he did want. If you look at Brian Clough’s career, a lot of the players he had came from down in the Fourth Division and he moulded them into a team. It wasn’t that they were bad footballers they were in the Fourth Division, but he moulded them into what he wanted. He was a hard man, he was a strict man but by God he knew his onions, he knew what was what. I don’t think he asked anybody to do anything that he wouldn’t have done himself.

And some of the other managers who were big personalities – Matt Busby at Manchester United?

He could put together sides. British lads. He shopped around, he found players. He was good. So was Bill Shankly. They were good managers. They’d got the skill of man-management, which was more than just being there as a figurehead – ‘look how good I am’. They were man-managers, they could manage people and mould players into what they wanted and that’s what it’s all about.

The final one on that, probably the most controversial team of that period, Leeds United under Don Revie. How did you feel about them?

I thought they were a hard team, but they played to their strengths. They had one or two hatchet men to say the least but they could be beaten. And they did get beaten but you’d got to hold your guns and let them come on at you, and make fools of them when they came. You can have your Billy Bremners and Norman Hunters and all of them, but Johnny Giles was the hatchet man and he would kick anybody or anything. But that was part of the game. They ruffled a few feathers but it worked and you can’t ask anything more than that, can you? That’s what it’s all about, making a system work. But now there is no system, only the one system, which is number one coaching and everybody plays the same so unless you’ve got a big cheque book, you’re going nowhere.

At what point would you say the major change has been in English football, say from what we have been discussing to what we’ve got now?

I think the big decline came to football, the start of it, when the [maximum] wage was altered. I know it wanted altering but it was altered too much. Now you see players who are non-entities walking away with £50 million, some are on £300 thousand a week. I mean, where are we coming from? A million pounds for four games and I’ve seen far better players than all of these are. I think that was the start of it when George Eastham took them to court, and I think the next stage was when we decided we would bring foreign players in. Foreign players didn’t want to come cheap, so wage inflation started. It’s just mushroomed from there. Nobody can tell me that a football player is worth £300,000 a game.

What about the influence of television, that was something that wasn’t really there at all when you were starting to watch football – maybe the F.A. Cup Final would be about the only football you’d see? So what’s your experience of that change?

It was in black and white – yes. I think there’s too much of it now, there’s too much coverage of football, so-called football, as I call it. I think it’s just a showpiece for the egos of a lot of people. I don’t believe that you need all the back-room staff and all the hangers-on for a game of football. There are more back-room staff than there are players. I think the players go on and they’re preening. It’s all play-acting now, it’s all like a soap opera. I mean if you were kicked in the old days, you stopped down and if you couldn’t get up, you stopped down and somebody would carry you off. Not with a stretcher, they’d just carry you off. But when you were injured in the old days, the trainer used to run on with a sponge and a bucket of cold water. When you saw him coming on a frosty day, you got up. You didn’t want that round you. But now one minute they’re rolling round in agony for the sake of television, and the sake of getting people booked and sent off. All to do with showbusiness. And I just can’t get my head round it at all. One minute they’re there in agony, as though they’ve broken their leg and as soon as the ref’s gone or he’s got a card out or booked him or whatever, he’s up again and he’s as right as rain. Now I call that cheating. I don’t like the way football’s gone. I’ve loved football all my life, but now I’ve come to the point where I’m watching it and I think ‘switch it off’ and I just don’t watch it because it bores me to death.

Could you pick a single aspect of English football that’s been improved by the Premier League?

The only thing that I can say has improved in football are the pitches, they’re like billiard tables. If you can’t play football on there, you’ll never play football. You must be able to play football on those pitches. I mean try playing with an old ‘number five’ ball on a muddy pitch on a November / December’s day when it’s snowing, and you can’t see the lines – try playing in that. I mean everything’s geared to the players now, they play in bedroom slippers.

To end up with some of your favourite memories, maybe a particular game or memory that would stand out for you of football at its best?

Obviously the League Cup Final has got to be one of the best, when we [Stoke City] beat Chelsea in 1972. I enjoyed that. I enjoyed it more because I stayed in the same hotel as the team and went to the reception afterwards – the players were with you then, they were great. They used to talk to you all together. I was very fortunate though because I had a friend, Michael Axon, whose father Percy was a Director of the club. I could get tickets and I could get access where a lot of people couldn’t. On the same bus as the Director. Oh aye, a different game. I enjoyed my football, I enjoyed watching football.