Football in North America: The Background

Football in North America, or soccer as our trans-Atlantic cousins prefer to call it, has a longer history than many people imagine. Canada and the USA contested the first international fixture outside the British Isles, at Newark, New Jersey, in 1885, where a group of British expatriates had established the American Football Association, the world’s fourth such national association, a year earlier. In Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario, Canada, the Western Football Association was formed in 1880. Galt Football Club of Ontario won the first gold medal for football at the 1904 St Louis Olympics; teams representing US colleges won the silver and bronze medals. Recognised by FIFA in 1913, the American men’s team played their first ‘official’ fixtures under the auspices of US Soccer in August 1916, against Sweden in Stockholm. Various fledgling, semi-professional leagues had existed before the formation of the American Soccer League (ASL) in 1921, consisting of eight teams in Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island, which flourished in the following decade.

Colin Jose, the great historian of this era, described it as a ‘golden age’ of American soccer; the ASL was centred in the industrial heartland of the East Coast, where it had a ready and vast audience of recent European immigrants with an attachment to the sport, and could be sustained by booming mill towns and wealthy owners. With teams such as Bethlehem Steel, Boston Wonder Workers, J & B Coates, Fall River Marksmen, Indiana Flooring Co and New Bedford Whalers enjoying the backing of these corporate sponsors, the US’s first professional league was both competitive and financially powerful. Owners such as Charles Schwab at Bethlehem Steel and Fall River’s Sam Mark even paid for the construction of purpose-built stadia, with the latter regularly reaching its 15,000 capacity; such attendances rivalled those for ‘gridiron’ in the National Football League. Its early success prompted the ASL’s Vice-President Thomas Cahill to declare that “soccer is making great progress and in the not too distant future will rank second only to baseball as the leading pro game.” This high-scoring league indeed went from strength to strength in its early years, expanding to twelve teams in 1924. The American game also saw innovations ahead of their time such as substitutions and the introduction of numbered shirts, worn for the first time by St. Louis Vesper Buick in the 1923-24 National Challenge (US Open) Cup Final against Fall River Marksmen.

The ASL, having gained prestige and spending power, attracted a number of players from Europe to North America, including Herbert Carlson of Sweden, Hungarian Janos Nehadoma and Werner ‘Scotty’ Nilsen, born in Norway but who played for the US in the 1934 World Cup. British players too were tempted by wages far greater than on offer in the UK, plus the promise of employment by their club’s parent company. Harold Brittain left Chelsea for a successful career in the States, while Scots formed the bulk of the ASL’s imports. One of the League’s strongest sides, Fall River, brought Tommy Martin and winger Jimmy ‘Tec’ White from Motherwell, together with Scots Charlie McGill and Bill McPherson, to play in the Championship-winning sides. Rivals Bethlehem Steel boasted the Scottish winger Alex Jackson, later scorer of a hat-trick for the ‘Wembley Wizards’, together with his compatriots Tommy McFarlane, Daniel McNiven and Jimmy Young. The Boston Wonder Workers eclipsed even those signings when another international, Tommy Muirhead arrived from Rangers as player-manager in 1924. Though he only stayed a year before returning to Ibrox, Muirhead was instrumental in perhaps the greatest coup of all, bringing Scottish international Alex McNab from Greenock Morton. McNab was signed for $25 a week to play and work at the Wonder Works factory. This influx led to complaints from European clubs, with ASL owners often ignoring existing contracts, and the Scottish FA demanding action against the ‘American menace’. In response, FIFA summoned the secretary of the ASL to their 1927 Annual Congress in Finland and, under threat of expelling the US Football Association (USFA), an agreement to regulate international transfers was negotiated.

The ASL’s most celebrated goalscorer was arguably Archie Stark; born in Glasgow, his family moved to New Jersey when was he was 13 and, after playing for a number of teams, he established himself at Bethlehem Steel and set a scoring record with 70 goals in the 1924-25 season. Alongside the league’s imported players was a core of home-grown talent such as Davey Brown, Billy Gonsalves, reckoned to be the ASL’s most gifted player, and Bert Patenaude, a trend which grew after the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 curbed immigration to the US. It was Patenaude who made history as the scorer of the first hat-trick at 1930 World Cup as the USA reached the semi-finals and finished in a creditable third place. After heavy defeats to South American giants Uruguay and Argentina at the Olympics of 1924 and 1928, the performance of the national side at the inaugural World Cup was testament to the strides made in the years of the ASL. Liverpudlian George Moorhouse, who had played briefly for Tranmere Rovers before emigrating and becoming a naturalised American, was the first English-born player at a World Cup finals. The 1930 squad contained a further five players born in Scotland, a Scottish coach, Robert Millar, and Irish trainer Jack Coll but contrary to popular myth, was not composed of British professionals.

Archie Stark

Bert Patenaude, USA

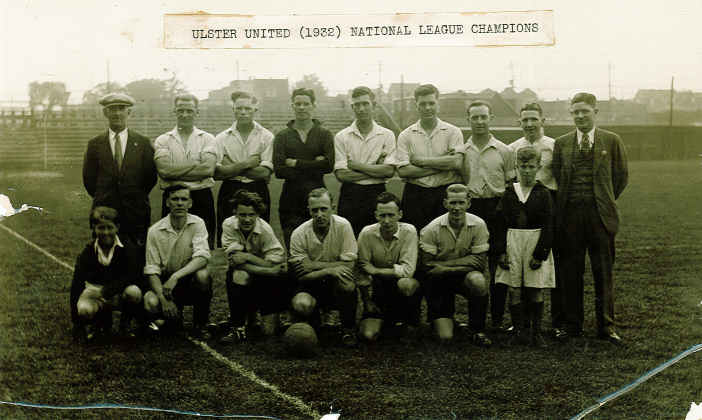

North of the border, the game’s initial impetus came from British ex-pats; the Caledonia Football and Athletic Club of Calgary was formed in 1904 by exiled Scots, who decided “the colours to be the black and white of Queens Park.” As soccer spread across the country, British Columbia saw the country’s first ever professional game, played at Vancouver’s Recreation Park on March 25 1910, between the Rovers and the Callies. After several years in which each province ran their own competition, the Canadian National League was established in 1926; its fortunes rose and fell in tandem with the ASL. It had a similarly high proportion of British-born players, reflected in its prominent clubs such as Toronto Scottish, Toronto Ulster United and Hamilton Thistles, alongside those representing companies such as the Canadian National Railway and Montreal Carsteel.

Though it also fell into decline during the 1930s as the financial crisis across North America hit the factories which had bankrolled many clubs, the Canadian National League continued until 1997, while Canadian clubs competed in the NASL, where the Toronto Metros-Croatia, led by Eusébio, won the 1976 Soccer Bowl. Another successful franchise was the Vancouver Whitecaps, where a young Peter Beardsley and Bruce Grobbelaar gained experience. The Canadian national team, FIFA members since 1924, have only qualified for a single World Cup, the Mexico tournament of 1986.

As in Canada, the Wall Street Crash and Great Depression were the main contributors, but the ASL’s demise was hastened by the internal battle known as the ‘Soccer Wars’ which ultimately finished it off. It began with a dispute over participation in the 1928 US Open Cup, the League believing the competition was disruptive and an unnecessary burden to its clubs, which then withdrew from the Cup. The lingering resentment between the USFA and the ASL had only grown since the confrontation with FIFA over European transfers, and several club owners openly sought to escape the control of the governing body. However, in this instance, three clubs – Bethlehem Steel, Newark Skeeters and the New York Giants – defied the League and entered the Open Cup, only to find themselves banned by the ASL. The USFA retaliated by suspending the League, which continued under ‘outlaw’ status, minus the three banned teams who joined the newly-formed rival Eastern Soccer League. Though the dispute was resolved a year later the ASL, its clubs and owners suffering from the economic crisis of the 1930s, never recovered, and folded in 1933.

Over the following decades, soccer in North America largely reverted to amateur, regional leagues and college teams, where it remained in the shadows of baseball, basketball and American Football. Unable to fill the gap left by the ASL’s demise, the USA would have to wait the best part of four decades for another successful professional league. Another incarnation of the ASL was formed immediately, paying much lower salaries and dominated by ethnically-based clubs such as Kearny Irish and Scots, Newark Germans and Brooklyn Hispano; largely confined to the Northeastern United States, it managed to continue until 1983, although almost totally eclipsed by the NASL in its last years. After their success at the first World Cup in 1930, the US national team played a single game at the 1934 tournament, a 7-1 thrashing by the hosts and eventual winners, Italy, under another Scottish coach, David Gould. They next reached the 1950 finals in Brazil; by now the squad contained players born not only in England and Scotland, but Belgium, Haiti, Italy and Poland, and a Scottish coach in Bill Jeffrey. Though they achieved a sensational 1-0 victory over England at the group stage, that proved to be their only victory, and they did not qualify for another World Cup Finals until 1990.

The Encyclopedia of American Soccer History, 2001

Soccer in a Football World, 2006

Three authors who have exhaustively documented the history of football in North America are Colin Jose, David Litterer and David Wangerin. Colin Jose was born in England and as the author of nine authoritative books, including American Soccer League 1921-1931, he is regarded as the foremost historian of US soccer. David Litterer maintains the comprehensive US Soccer History Archives, which proved invaluable in my research for this project, and has written numerous articles. The late David Wangerin was the author of Soccer in a Football World: The Story of America’s Forgotten Game and a follow-up, Distant Corners: American Soccer’s History of Missed Opportunities and Lost Causes. Both chart the development of American soccer from its origins, through the ‘golden age’ of the 1920s, the lean years that followed, into the NASL era and beyond. Roger Allaway and Steve Holroyd are also among the most highly-regarded historians of the American game.

Great article and look back at what a fantastic and innovative league the US had back in the 1920s.

Thank you James, it was a very enjoyable one to research as it was almost entirely new to me, and contained some great stories! I’m hoping to put together a series of posts on North America, bringing the history up to date.