South America: Foreign Players in the Football League

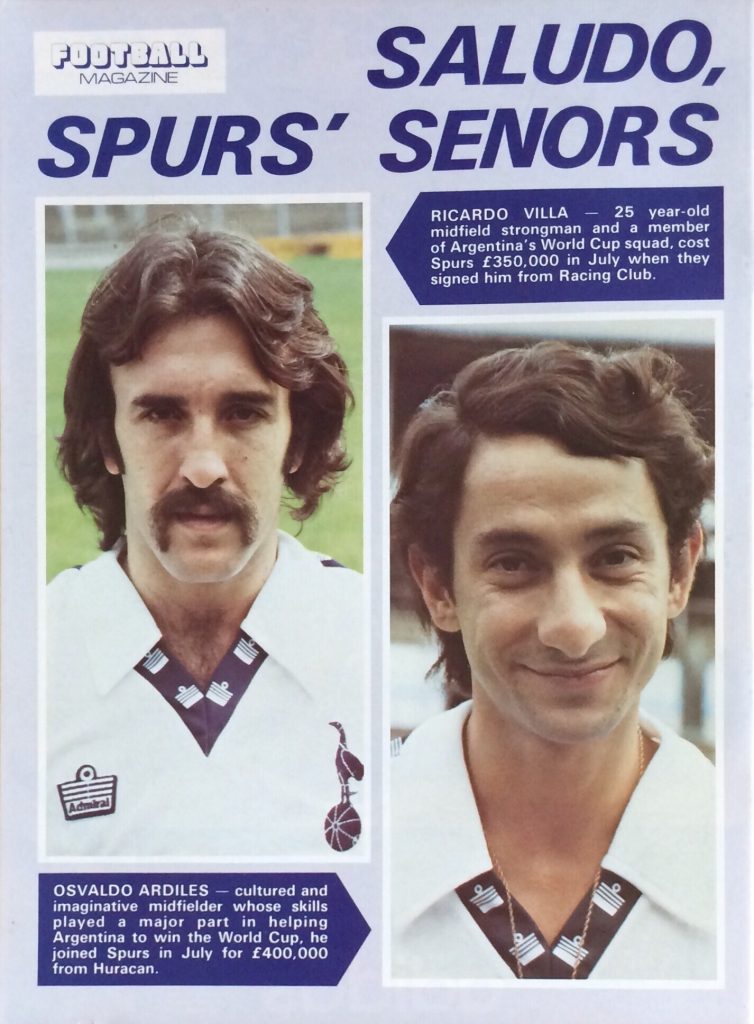

South America reinforced its credentials as the strongest footballing continent when Argentina lifted the World Cup for the first time on 25 June 1978 at the Estadio Monumental, Buenos Aires. By beating the Netherlands 3-1 to win the tournament they had hosted, Argentina joined neighbours Brazil (three times winners) and Uruguay (twice) as World Champions in six of the eleven tournaments to date. Within weeks two members of their squad would join Tottenham Hotspur, arriving in the Football League to begin a new chapter in English football history.

While the dramatic signings of Ossie Ardiles and Ricky Villa were welcomed by many, opponents of an influx of South Americans included PFA Secretary Cliff Lloyd, who was worried that the transfer trend for foreign players “could spread like wildfire”. How players from across the Atlantic would cope with the English climate, culture and language barrier – and manage to thrive on the mud-bath pitches of the day – was the subject of much speculation. Was it possible for the new arrivals to make a successful transition from South America to England?

The British had been heavily involved in the origins of football in South America, but this was the first time the relationship was reciprocated. As the historic Football League restrictions on foreign players were lifted in the summer of 1978, simultaneously Argentinian footballers were now allowed to leave the country – the Argentine FA lifted a ban on exporting players which had been put in place to help coach César Luis Menotti prepare for the World Cup.

The first English manager to explore the newly available market was Sheffield United’s Harry Haslam. His contact in Argentina was the notorious 1966 World Cup captain, Antonio Rattín, and he worked with coach Oscar Arce [Fulloné] at Sheffield United. Haslam alerted Tottenham manager Keith Burkinshaw to the availability of World Cup winners Ardiles and Villa, who were priced beyond the Second Division club’s budget. It was still a spectacular coup when they brought play-maker Alex Sabella from River Plate shortly afterwards. Haslam would sign a second Argentine for Sheffield United the following summer, Pedro Verde (the uncle of Juan Sebastián Verón), who was nearing the end of his career and made little impression in the Football League.

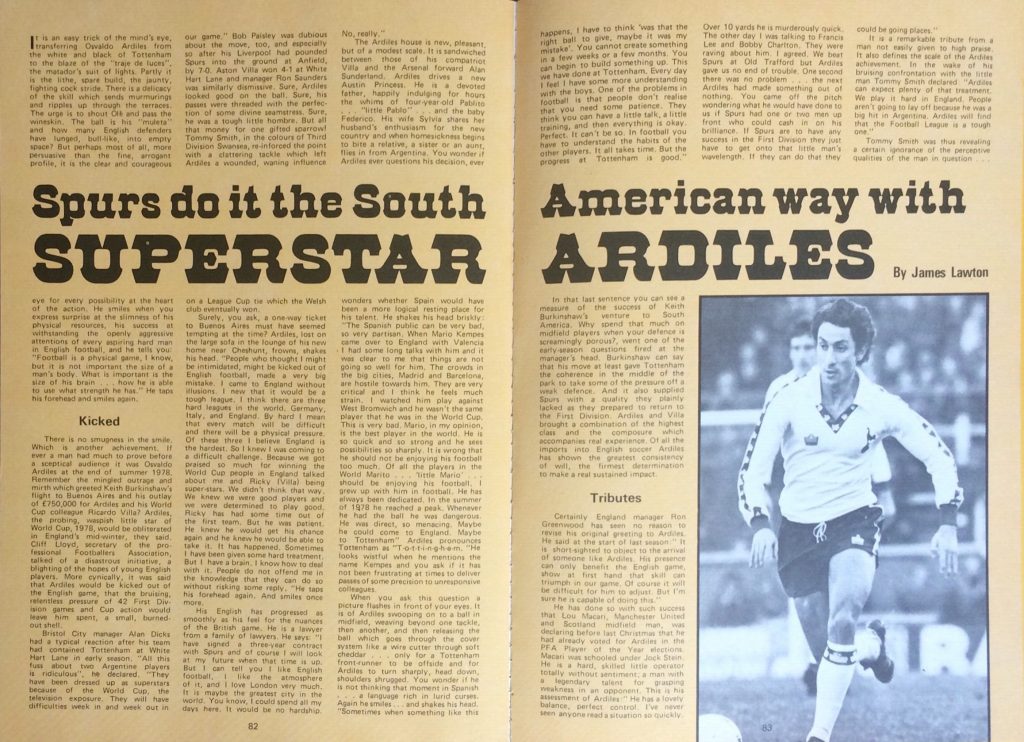

‘Spurs do it the South American Way with Superstar Ardiles’ (Shoot! Annual 1980)

Below: ‘The amazing story behind Tarantini’s transfer’ (Shoot! 1978)

Also helping to ease Sabella’s transition to English football was another South American on the coaching staff at Bramall Lane, Uruguayan Danny Bergara. Haslam was full of praise for him: “Danny’s influence on the team has been tremendous because of his coaching, his methods and his set ups.” The two had first worked together at Luton Town in the mid-1970s; regarded as an innovative coach, Bergara was later involved with England teams at youth level. He became the first manager in the Football League who spoke English as a second language, at Rochdale in 1988, before enjoying his greatest success in charge of Stockport County.

The gifted Sabella was unlucky to play for a struggling side in a lower division – Sheffield United were relegated in his first season and he spent 1979-80 in the third tier. He then joined a Leeds team in decline, battling relegation from the First Division at the start of the 1980s. On returning to Argentina with Estudiantes in 1982, Sabella became a championship winner and a national team player, winning eight caps in 1983-84. He took Argentina to the 2014 World Cup Final as manager before his untimely death in 2020.

Birmingham City unveiled another member of the World Cup-winning side early in the 1978-79 season, left-back Alberto Tarantini. The player was available when a move to Barcelona fell through, after a prolonged contract dispute with Boca Juniors. Tarantini’s brief 23-game First Division spell at Birmingham was an unhappy one, best remembered for him knocking out Manchester United’s Brian Greenhoff and fighting with a fan at his final game. It was no surprise when his stay ended even before the end of the season – with Birmingham destined for relegation, he returned to Argentina with Talleres de Córdoba. Details of his contract later revealed that Tarantini was on a basic weekly wage of £363, plus bonuses, with the club covering transport costs and living expenses for his family in England.

Tarantini’s miserable experience was echoed by Claudio Marangoni, who became Sunderland’s record signing when he arrived from San Lorenzo in December 1979. With Arce now on the coaching staff, Sunderland had attempted to sign Sabella in the summer of 1979, but returned to Argentina for Marangoni. While he was felt to be well suited to English football, the midfielder barely lasted a single season. Like Sabella, Marangoni went on to represent his country and win several trophies back in his homeland, notably the 1984 Copa Libertadores and Intercontinental Cup (against Liverpool) with Independiente.

Marangoni, Sabella and Tarantini’s misfortunes in England were in sharp contrast to the success of Ardiles and Villa, who had travelled as a pair, joined a stronger First Division side and had team-mates such as Glenn Hoddle on their wavelength. The inability of these undoubtedly talented individuals to adapt to the Football League illustrated the difficulties facing foreign players in that era. These early imports from South America had to overcome a very different social and sporting culture, homesickness, the language barrier, heavy pitches and the physical nature of the English game at the time, especially below the top level.

Below: Néstor Lorenzo, Argentina; Mirandinha, Newcastle; José Perdomo, Uruguay (Panini Italia 90)

No Argentine player arrived in England during the 1980s; over a decade had passed since Marangoni’s transfer when Néstor Lorenzo signed for Swindon Town from Italian club Bari. Ardiles, by now player-manager at Swindon, persuaded a player who had been part of the Argentina team beaten in the final of Italia ‘90 to join the Second Division club. However, Lorenzo was another Argentine unable to settle in the Football League. There was no further rush of Argentinians to the English game until Mauricio Taricco joined Ipswich Town in 1994, and later continued the tradition begun by Ardiles and Villa at Tottenham.

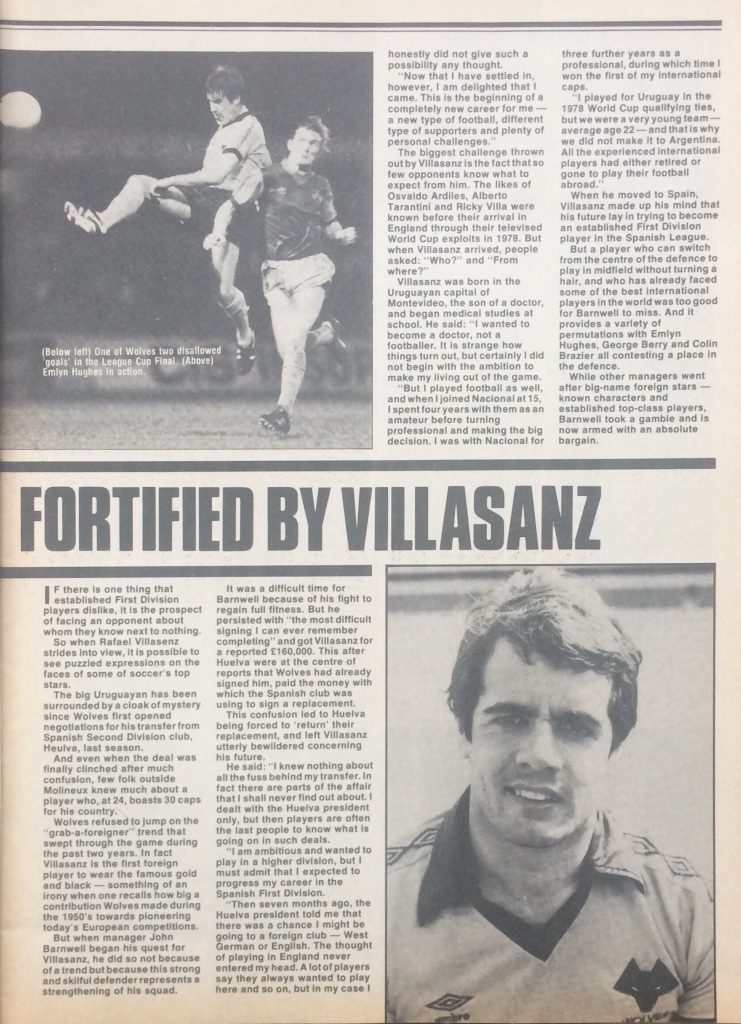

Amidst the high-profile Argentinian signings, a player from across the River Plate arrived with little fanfare. The first Uruguayan to play in England was a defender, Rafael Villazán, a solid rather than spectacular signing for Wolves in 1980. Lengthy negotiations brought him from Huelva in Spain for £140,000 in May 1980, manager John Barnwell dismissing worries that he spoke no English: “Football is international. He’ll soon learn.” Villazán was good enough to win 11 caps for his country and describes his time in England as “a great experience… I quickly adapted to the weather, the language and the game.” However injuries dogged his career at Molineux, and he returned to South America after Wolves’ relegation from the First Division at the end of 1981-82, later playing for clubs in Colombia and Paraguay.

It took another decade for Villazán to be followed by Uruguay midfielder José Perdomo, who had captained his country to victory in the 1987 Copa América before playing at Italia ‘90. Perdomo arrived from Serie A club Genoa for a short-lived (six-game) trial spell at Coventry City. The next Uruguayan in England was striker Adrián Paz, signed alongside Argentine Taricco by Ipswich Town as they prepared for the 1994-95 Premier League season. The double transfer from South America was negotiated with Marcelo Houseman, an agent who was the brother of 1978 World Cup winner René Houseman. Paz lasted only a season and scored a single goal.

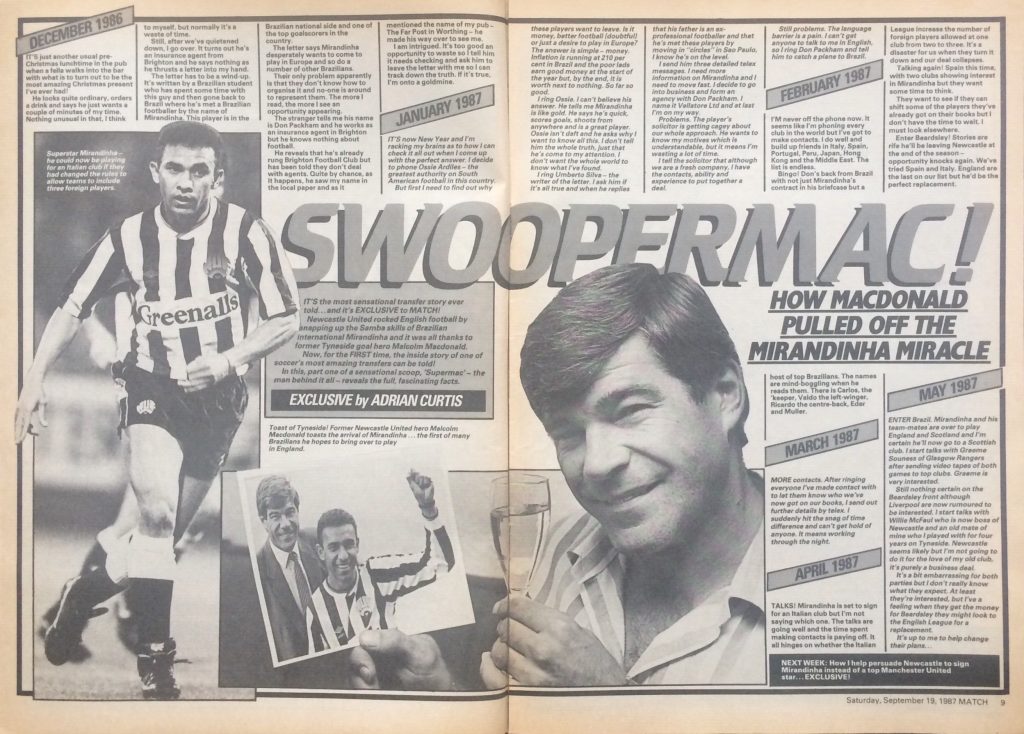

The first Brazilian didn’t arrive in English football until 1987; Mirandinha had scored for Brazil at Wembley in a friendly that May but wasn’t a first-choice player for his country. The striker signed for Newcastle in August 1987 with the help of Malcolm Macdonald, who promised to bring more Brazilians to England: “It will broaden the thinking of youth football in this country and the Football League will be better for it.” After a relatively successful first season at Newcastle alongside Paul Gascoigne, the striker and the team struggled in his second, which ended in relegation and his return to Brazil. The trail-blazing Brazilian remembers his time in England fondly: “Newcastle was the best experience of my life.”

Below: Reports on Dirceu’s non-transfer to Birmingham (Shoot! 1978/79), & Nunes to Everton (1983)

Mirandinha’s move might have been preceded a decade before, in the first wave of post-summer 1978 transfers. Before the 1978-79 season, negotiations were opened firstly by Birmingham with World Cup player Dirceu, and also in 1978 by Fulham with Paulo Cézar (‘Caju’). Neither deal came to fruition, as was the case later with Sunderland’s interest in another Brazilian 1978 World Cup star, Gilberto ‘Gil’ Alves. Speculation about Nunes, best known to English fans for his two goals against Liverpool in the 1981 Intercontinental Cup, moving to Everton on loan in 1983 reached the pages of Shoot! magazine. Despite manager Howard Kendall requesting “a video tape of his most recent games”, the striker remained in Brazil.

Not until the Premier League era was well underway in the 1990s was there any influx of Brazilians to the English game, in a much more accommodating setting. Mirandinha was eventually followed by Isaías at Coventry in 1995, and a batch of players at Middlesbrough – most notably Juninho, accompanied by Branco and Emerson in 1995-96. South America’s subsequent impact on the Premier League has been illustrated by multiple Champions and Golden Boot winners in Argentines Sergio Agüero and Carlos Tevez, and Uruguayan Luis Suárez. The only league-winning South American manager to date is Chilean Manuel Pellegrini with Manchester City in 2014.

While Chile had been represented decades earlier in England by the Robledo brothers, Javier Margas became the first player to arrive in the modern era when he joined West Ham in 1998. Brighton tried to bring Peru’s World Cup players Juan Carlos Oblitas and Percy Rojas to the Football League in early 1979 – despite reports that Oblitas had signed, the attempted transfer fell through. Another pair of Peruvians, Raúl Gorriti and Victor Hurtado, also had an unsuccessful trial at Leeds in 1980. Not until nearly two decades later was there finally a Peruvian in English football, with the signing of Nolberto Solano – another pioneer at Newcastle – in 1998.

It was only in the 1990s and even early 2000s that the first players from other South American countries also arrived in England: Bolivia (Jaime Moreno, Middlesbrough 1994), Colombia (Faustino Asprilla, Newcastle 1996), Ecuador (Agustín Delgado, Southampton 2001), Paraguay (Diego Gavilán, Newcastle 2000), Venezuela (Fernando de Ornelas, Crystal Palace 1999).

The arrival of players from South America to the Football League at the end of the 1970s is one of the topics discussed in my book Before the Premier League: A History of the Football League’s Last Decades.

Danny Bergara’s biography is The Man from Uruguay (2013) by Phil Brennan.