The Opening of Old Trafford

The opening of Old Trafford in February 1910 was a pivotal moment in the history of Manchester United. Today, they are one of the world’s most famous football clubs, and their home among the game’s iconic stadiums. Yet their origins were much more humble, and their early years often troubled. Their history began in 1878 as Newton Heath, funded by the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway; they played in regional cup competitions before joining the Combination and then the Football Alliance, both alternatives to the newly-formed Football League. Their home was at North Road until 1893, by which time they had been elected to the First Division of the Football League.

Newton Heath moved to Bank Street in the Clayton area of Manchester, adjoining the Albion Chemical works and local railway lines. A 10,000 crowd saw a 3-2 victory over Burnley on 1 September 1893 in the first game at the ground. However the opening season at Bank Street coincided with hard times – the pitch was the subject of regular complaints, and they were relegated from the First Division in 1894. After being served with a winding-up order, the club’s existence was threatened by early in 1902. They were reduced to public charity collections when an escaped St Bernard dog named Major, owned by club captain Harry Stafford, was found by the daughter of brewer John Henry Davies. Thanks to Major’s intervention, it was Davies who saved Newton Heath from liquidation.

Bank Street, home of Newton Heath and Manchester United

Bank Street Plaque

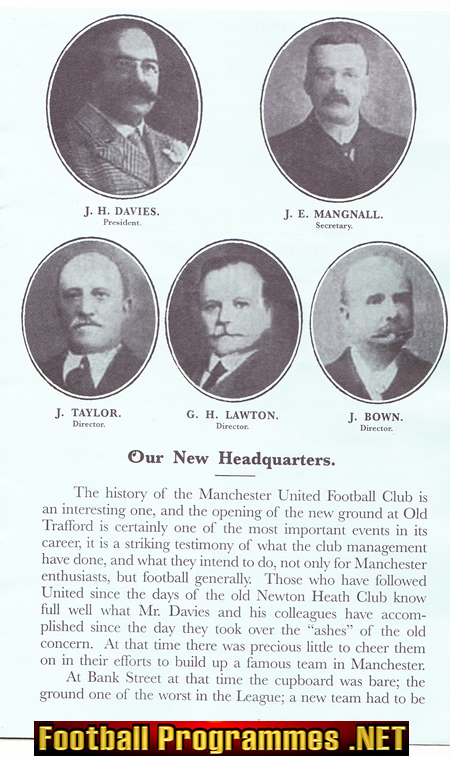

A new start was marked by their re-naming as Manchester United in April 1902, now playing in red and white rather than Newton Heath’s green and yellow. With their Bank Street stadium developed into a 50,000 capacity arena, they established themselves as a force at the top level under manager Ernest Mangnall, with star players such as Billy Meredith and Charlie Roberts. By 1908 they had won their first Football League Championship, followed by the FA Cup a year later.

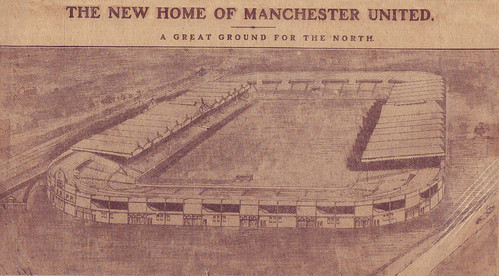

To match the growing ambition of Chairman Davies, the club prepared to leave Bank Street. They moved away from the limitations of a cramped stadium in an industrial district, across the city. The Old Trafford site five miles away, next to the cricket ground, was identified as their ideal location. For the biggest move in English football to date Davies commissioned the game’s greatest architect, Scottish engineer Archibald Leitch. Fresh from his work on Ibrox, Bramall Lane, Stamford Bridge and Craven Cottage, the 16-acre Old Trafford site offered Leitch a different, if lucrative, challenge. The cost of construction was estimated at £60,000.

J.A.H. Catton, writing under his pseudonym ‘Tityrus’ as the Editor of Athletic News in 1909, announced that “the club have resolved to lay out and equip a huge ground wholly and solely devoted to football. There will not be any running or cycling track round the grass, and for football alone there will not be a better enclosure in England.” Catton hailed Manchester United’s proposed stadium, then under construction, as “a palatial ground which will challenge comparison with any arena in Great Britain.” Anticipation had built even further by the time Bank Street’s final match took place on 22 January 1910 in front of only 5,000, shortly after which its main stand was destroyed in a gale.

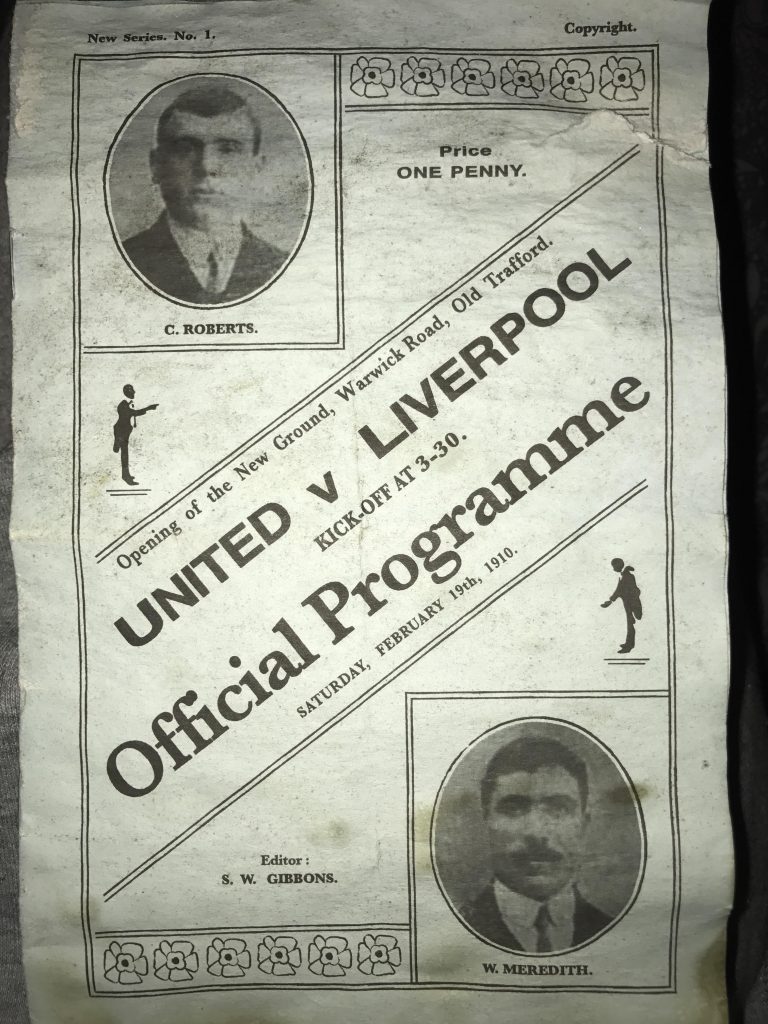

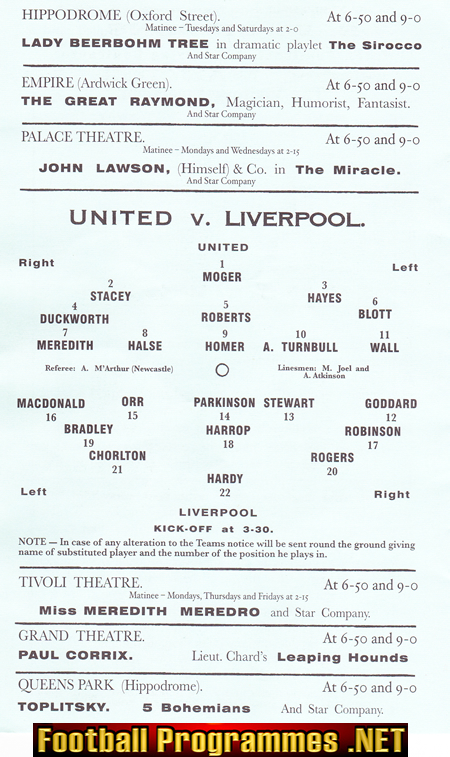

Confirming the prestige of the new stadium, Old Trafford was given a gala opening and widespread publicity ahead of the first game against Liverpool on 19 February 1910. An estimated 45-50,000 crowd saw United’s Sandy Turnbull score the first goal at the ground to help the home team establish a 2-0 half-time lead. Two strikes each from Liverpool’s Arthur Goddard and Jimmy Stewart led a second-half comeback as the game ended in a 4-3 win for the visitors, “a remarkable victory”. The Manchester Guardian praised both the grandstand (“a new luxury unknown till then”) and the pitch, which “after the years of mud and glue at Newton Heath – resembled the surface of a bowling green.”

As the club had hoped, Old Trafford was soon chosen to host an FA Cup Final, firstly the 1911 replay and then the 1915 ‘Khaki Cup Final’. It also became an international football venue when England met Scotland there in 1926, and has been hosting rugby league games since the 1920s. While the stadium itself was an undoubted success, it left Manchester United saddled with a hefty debt, and more tough times were ahead. After Mangnall led them to another title in 1911 – and soon left for rivals Manchester City – it would be over forty years before the League Championship returned to Old Trafford. In both the 1920s and 30s the club spent several seasons in the Second Division, returning to the top flight in 1938. Meanwhile, the 1939 FA Cup semi-final between Grimsby and Wolves saw a record attendance of 76,962 at the ground.

John H. Davies, Manchester United Chairman 1902-27

Ernest Mangnall, Manchester United Manager 1903-12

Second World War air raid damage caused the ground to be closed until 1949, during which time United shared Maine Road with neighbours City. It was at Maine Road that the record attendance in English League football was set on 17 January 1948 – 83,260 for United’s First Division match against Arsenal. The club’s resurgence came under Matt Busby, who secured the long-awaited third League title in 1952, and followed it with four more before he led United to become the first English club to win the European Cup, in 1968. Old Trafford hosted fixtures at the 1966 World Cup, the 1996 European Championships and the 2012 Summer Olympic Games, and was chosen as the venue for the 2003 Champions League Final.

Match details for Manchester United – Liverpool, 19 February 1910:

Manchester United: Moger, Stacey, Hayes, Duckworth, Roberts, Blott, Meredith, Halse, Homer, Turnbull, Wall. Manager: Ernest Mangnall. Scorers: Turnbull, Homer, Wall

Liverpool: Hardy, Chorlton, Rogers, Robinson, Harrop, Bradley, Goddard, Stewart, Parkinson, Orr, McDonald. Manager: Tom Watson. Scorers: Goddard 2, Stewart 2

Quotes from Athletic News and the Manchester Guardian are reproduced from Engineering Archie: Archibald Leitch – Football Ground Designer by Simon Inglis (2005).

Brilliant history!

Thank you, Adam!