Foreign Players in the Football League: Introduction

The Football League was made in England and founded by a Scot, William McGregor. The world’s first professional league flourished from 1888 with the contribution of Scottish, Welsh and Irish talent. While Britain exported the game worldwide, for much of its history foreign players in the Football League were a rarity. That changed permanently in the summer of 1978.

From the beginning, the Football League had sought to protect its local, and national, characteristics. For the very first season of the League, in 1888, there was a stipulation that players had to either be born within six miles of the club’s ground, or been resident within that area for two years. The regulation did not prevent clubs bending the rules to bring in an influx of Scottish professionals, at that time regarded as technically superior to their English counterparts. The Athletic News annual of 1890 carried an editorial (‘The Seamy Side of Professionalism’) complaining that “the buying up of ready-made talent from another country [Scotland] has practically stifled native effort.”

The nominal residence requirement was soon relaxed, and a Canadian of Swiss heritage, Walter Bowman, is credited as being the first foreign national to play in the Football League, for Accrington in 1892. The early League saw even more unlikely arrivals in the form of German Max Seeberg, who made a single appearance for Tottenham in the 1908-09 season, and Egyptian Hussein Hegazi who played briefly for Fulham three years later. Chelsea’s first foreign player, Dane Nils Middelboe, an amateur who represented his country at three Olympic Games, arrived in 1913; these early pioneers were of course isolated examples.

An attempt in 1930 by Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman to sign Rudi Hiden, an Austrian goalkeeper, was the catalyst to formally limit foreign players in the Football League. Charles Sutcliffe, later to become League President, led the outcry, declaring “The idea of bringing foreigners to play in league football is repulsive to the clubs, offensive to British players and a terrible confession of weakness in the management of a club.” The Ministry of Labour supported the Football League and Players’ Union in enacting the formal regulation, in June 1931, which was definitive in restricting imported players for the best part of five decades:

“A professional player who is not a British-born subject is not eligible to take part in any competition under British jurisdiction unless he has a two years’ qualification”.

The overseas players who made their way to the Football League remained exotic exceptions, such as the Chilean-born Robledo brothers – George was an FA Cup winner and First Division top scorer with Newcastle. The Second World War led to the arrival of prisoner of war Bert Trautmann, who became Footballer of the Year in 1956. Emilio Aldecoa, the first Spanish player in the Football League, arrived as a refugee from the Spanish Civil War. The bulk of imports were Commonwealth citizens (mainly South Africans, including Albert Johanneson, the first black player to feature in an FA Cup Final, for Leeds in 1965) and Scandinavians, playing as amateurs. Domestic regulations ensured it largely stayed that way up until 1978, when European legislation on freedom of movement superseded league rules.

Below: L) Bert Trautmann of Manchester City; R) Albert Johanneson of Leeds United

A ruling by the European Community in February 1978 determined that a player’s nationality could not affect their ability to move to any given country. The Football League AGM that summer duly lifted the effective ban on foreign players. The first arrivals in a wave that would grow in the following months and years came after the World Cup took place in Argentina.

10 July 1978 was a momentous day in the history of English football, as Tottenham Hotspur announced the signings of two members of the victorious Argentina squad – Osvaldo ‘Ossie’ Ardiles and Ricardo ‘Ricky’ Villa. They were soon followed by another Argentine, Alejandro ‘Alex’ Sabella at Sheffield United, Yugoslav Ivan Golac at Southampton, and Dutchman Arnold Mühren at Ipswich. It is hard to imagine how exotic these players were in the Football League of the late 1970s, a very different time and place than today’s multi-national Premier League.

There was of course controversy and mixed opinions expressed at the highest level, although England manager Ron Greenwood was enthusiastic about the first arrivals: “They have acted as a stimulant on our soccer. They have created a feeling of expectancy, excitement and glamour. To deny clubs work permits for their foreign players is a head-in-the-sand attitude.” The players’ union, the PFA, naturally held an opposing view, summarised by executive committee member (and future chief executive) Gordon Taylor: “If the trickle of foreign players becomes a flow, it could be detrimental to our members.” Taylor emphasised “the wider issue of the possible effect on the future of English football.” An attempt was made to restrict further imports, with a temporary ban imposed at the end of July 1978. A compromise was agreed between the Sports Minister, the Department of Employment and the PFA, allowing work permits to be granted to ‘established players’, limited to two per club.

The reasoning was explained in a parliamentary response by John Grant MP, of the Department of Employment, regarding Sheffield Wednesday’s attempt to sign Yugoslav Mojaš Radonjić: “The application … for a work permit … was refused because the player did not satisfy the conditions that I announced on 28 September 1978 for the issue of permits for overseas footballers. Permits are issued only for players of established international reputation who have a distinctive contribution to make to the national game. According to the club’s application, Radonjić had never played for his country in a full international and therefore could not be regarded as having an international reputation.”

World Soccer writers Brian Glanville and Keir Radnedge both welcomed the players who did arrive, though were dubious that they would set a trend (each citing the culture and language barriers alongside the UK’s high taxes). Glanville felt the first Argentinian signings represented “a bizarre and delightful aberration” while Radnedge cautioned that “later on there may be cause for concern at whether a larger influx is likely to be harmful to home-grown talent”. Writing in Football (Monthly), Paul Weaver was one of many to question how the newcomers would cope with the physical aspect of “the most fiercely-contested league in the football world”. Weaver wondered how Ardiles and Villa would fare “on a soggy Baseball Ground in November, or in ankle-deep mud at Stamford Bridge in December?”

England and Liverpool’s Ray Clemence felt few would follow them, while team-mate Phil Neal believed they were “a welcome addition to our game” – a view supported by fellow players such as Andy Gray and Gordon Hill. Ipswich boss Bobby Robson, who succeeded Greenwood as England manager in 1982, was another advocate of imports, signing Dutchmen Mühren and Thijssen during the season. Everton boss Gordon Lee was sceptical of foreign signings, as was Arsenal’s Terry Neill (though he did travel to Argentina on an unsuccessful search for players in June 1979).

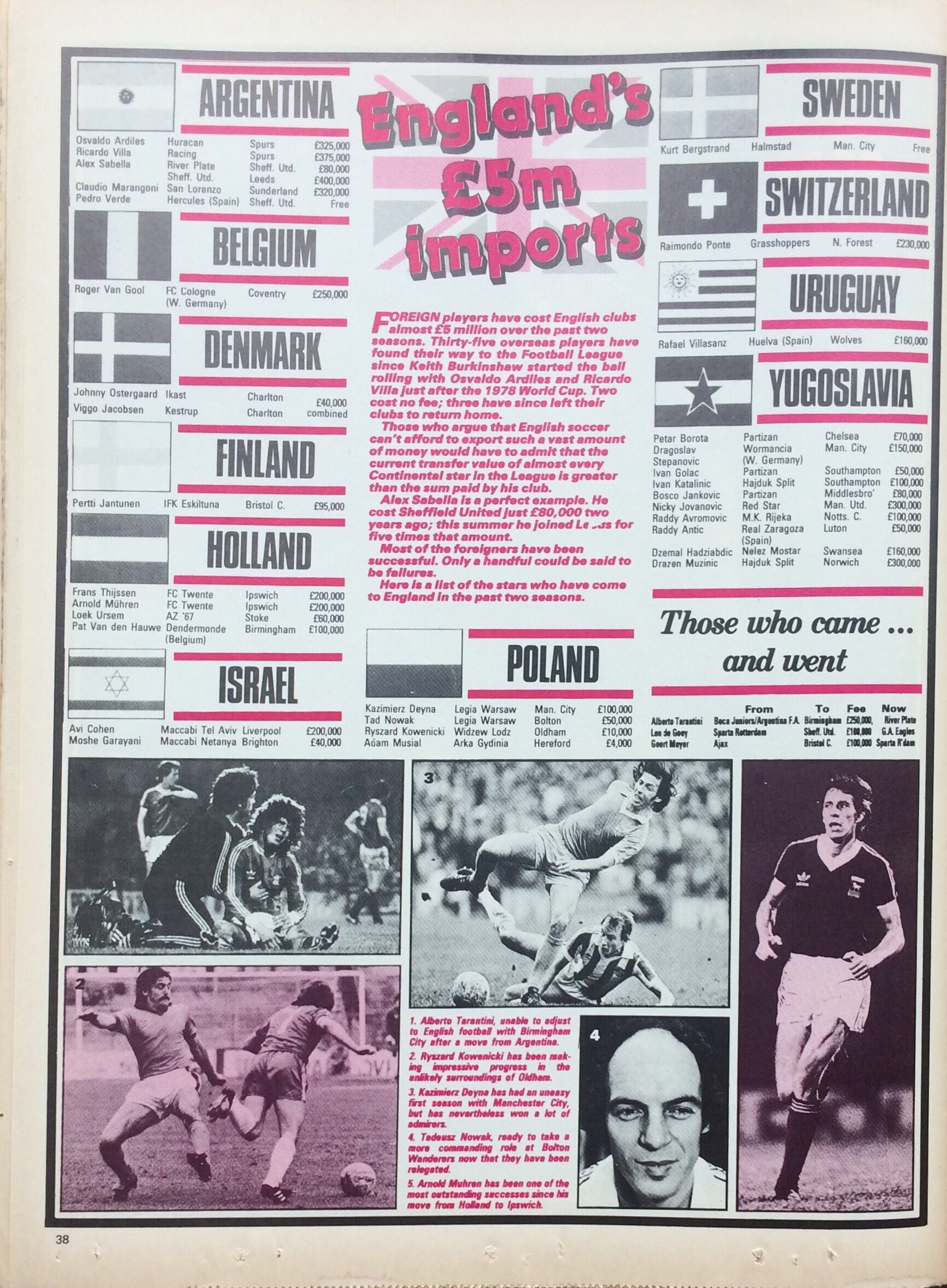

During the course of 1978-79, further arrivals from Argentina, the Netherlands, Poland and Yugoslavia made it clear that there was no going back. The First Division saw a total of 13 foreign players during the season (plus Sabella in the Second) – a handful flourished but not all of them settled in the Football League. As further transfers took place over the following years, the concept of importing players continued to be the subject of much debate and discussion. It was English football’s troubles on and off the field during the next decade – marked by falling attendances, financial struggles, hooliganism and the ban from European competition – which served to limit the flow of Football League imports. By the summer of 1983, Shoot! magazine was declaring ‘the end of an era’ of foreign players arriving in England.

Before the Premier League, players arrived from only a limited number of mainly European countries – Argentina was the exception, as the only other South Americans were a single Brazilian and two Uruguayans. Africa and Asia provided very few imports to the Football League, and even within Europe it was notable that virtually no top players came from France, (West) Germany, Italy or Spain. The Premier League kicked off with only 13 players from overseas appearing among the 22 clubs in the opening fixtures. Foreign managers – let alone owners – were still not even a factor. It is now a very different world, where management and ownership structures are foreign-dominated, domestic home-grown players are the exception at England’s leading clubs and over 100 nations have been represented in the Premier League.

By the time Chelsea fielded the first all-foreign starting XI in English football history for their 1999 Boxing Day fixture at Southampton, the issues raised echoed the 1890 Athletic News editorial: “Whether this process of importation and spoilation has been beneficial or otherwise to football itself is a very open question”.

With the help of experts and historians from various countries, over following posts I will focus on the post-1978 transfers to the Football League, both successes and failures. Many more moves were negotiated or rumoured, and I will look at some of the most prominent – from Cruyff and Maradona to Kempes and Krol. The contributions of individual players in English football will be discussed, together with wider trends.

With thanks to staff at the National Football Museum’s Collections & Research Centre at Deepdale, Preston, for access to research materials.

Nick Harris’s 2003 book England, their England is a comprehensive study of foreign footballers in the English game since 1888.

This series expands on the history of foreign players in the Football League, one of the topics discussed in my book Before the Premier League: A History of the Football League’s Last Decades.